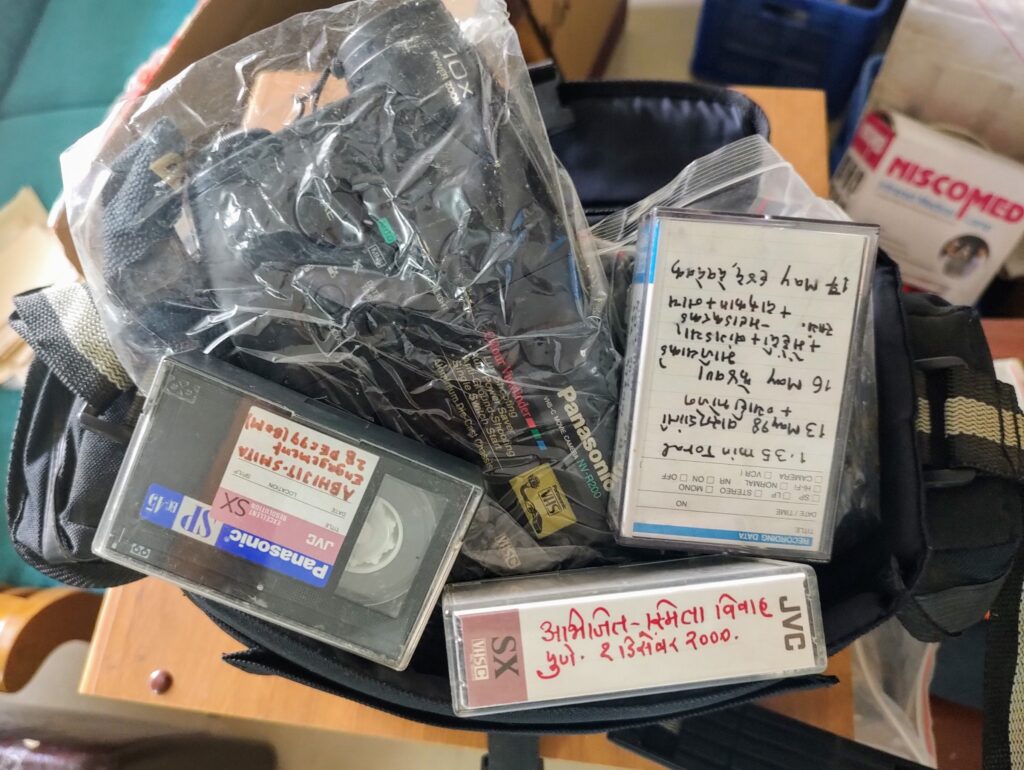

Since Abhi died in September 2001, Maa and Baba have held on to his things. Indeed, since Nana (my paternal grandfather) passed in 1994, and then my other grandparents did over the years, Maa-Baba have steadily accumulated papers, receipts, documents, bills, letters, manuscripts, training notes, teaching notes, photographs (8 trunks, yes, 8 steel trunks of the kind used by military officers to move their homes, full of almost 10,000 photographs clicked over the past 100-odd years), negatives (if you are born after 1990, you may not know what this means), even ticket stubs, interview and call letters, resignations, payslips, bank deposit slips and withdrawal slips, cheque stubs and passbooks, tax returns and refund acknowledgements, even uniforms, ranks, caps, shoes, tools and hardware including locks, keys, chains, hacksaws, pliers, entire spanner sets (yes, that’s plural), screwdriver sets (plural again), woodworking tools, and electronics ranging from machines that print out your name on a small sticker to drill machines to multimeters to scanners to printers to cameras (3 still and 2 moving, each with a tripod; yes, each) to television sets (yep, plural), and boxes, files, bags, briefcases, and suitcases filled with assorted clothes, abovementioned documents, Masters’ theses, project reports, and close to 5,000 books on subjects as varied as religion, military strategy, sex, history, philosophy, humour, autobiographies, fiction, comics (and this this does not include several copies of books written/translated by my grandfather, aunts, grandmother, mother, and granduncles). Then, there are coins and currency from across the world, wallets and folios, files and folders, pens, pencils, erasers, sharpeners, punches, staplers, markers (both permanent and whiteboard), OHPs (sorry again, if you are born after 1990), floppy disks, music tapes, VHS tapes (in all sizes), printer papers (yes, even the dot-matrix ones), envelopes, greeting cards, along with DRAM chips, motherboards (yes, entire motherboards), monitors of varying sizes, projectors (yep, plural), a foot massager, 2 golf sets, 3 squash racquets, a goods trolley, a garden umbrella, couple of dozens of plastic crates, several step ladders, and hundreds of kilograms of stuff that has now reached epic proportions, especially when it comes to shifting to a new home which is no longer on a smallish farm.

Why am I telling you this? Because, since my mother and I are shifting into the same house, and this house is a small flat in the city as opposed to where she was used to staying for the past 2 decades, it has fallen upon me to sort and discard stuff to make space, and restore sanity.

I have been after Maa for the past 3 years, since Baba passed, to sort the mess and clean it up. She has steadfastly refused. And after much consternation, I took it upon myself to do it this morning. Only about 60% of the total stuff is at the new house since we literally ran out of space while shifting, and had to leave the rest of it, about 40%, back in the old house where I would need to sort it out ‘on-site’ so to say. Just looking at those boxes piled high, those suitcases crammed shut, those crates overflowing with assorted things, those military-grade trunks padlocked with rusted locks for which keys had to be refashioned from a locksmith, made me swear under my breath about these oldies who cannot seem to forsake their past, however heavy that baggage, in every way. The greed to hoard and the refusal to let go, I told myself, is something I will never have. I do not want to leave a pile of irrelevant, unwanted, and probably useless crap for my progeny to sort through after I die.

Vowing to be different, I plunged into the job at hand: to mercilessly cull the excess shit we’ve been carrying for the past 30 years at the very least. I was hoping to get through it like a hot knife through butter. Basically, I had expected that Vikas and Geeta would open stuff and show it to me, and at one glace, I shall tell them if it has to be sold to the scrap dealer, donated to the poor, given away to friends, discarded in the trash can, or burnt to protect the privacy of those involved in the correspondence (or to not be culpable under the Official Secrets Act, given that both, my father and my brother, were serving in sensitive positions in the Government of India). So, off we went. I stood at one end of the room, and Vikas at another, with Geeta covering the flanks. The first bag was opened.

And it hit me.

There’s a reason why Baba, and after him, Maa, refused to do this. This is an impossible task. It is hugely draining on one’s spirit and stressful to the heart. It is something that draws you in. And then, crushes your soul.

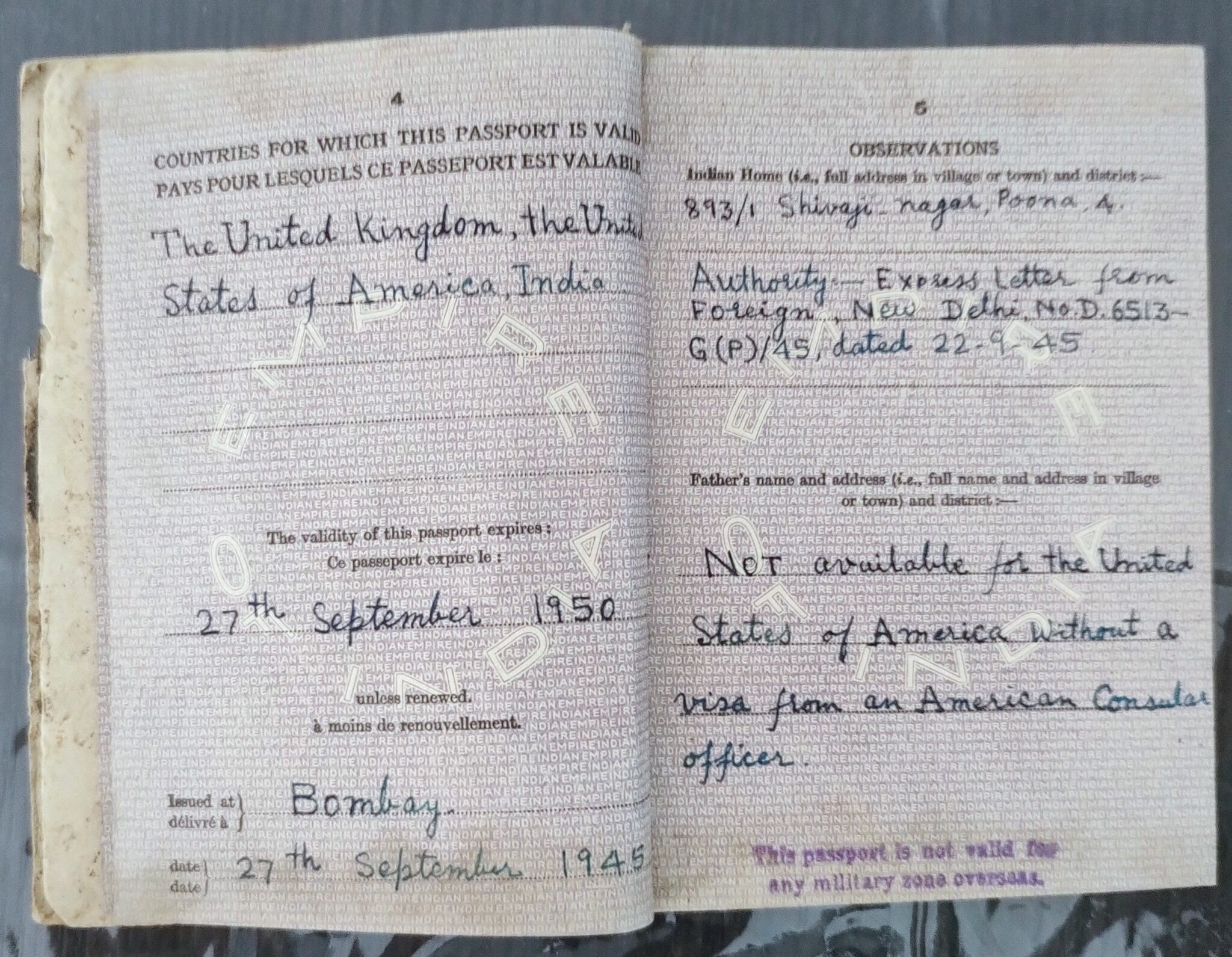

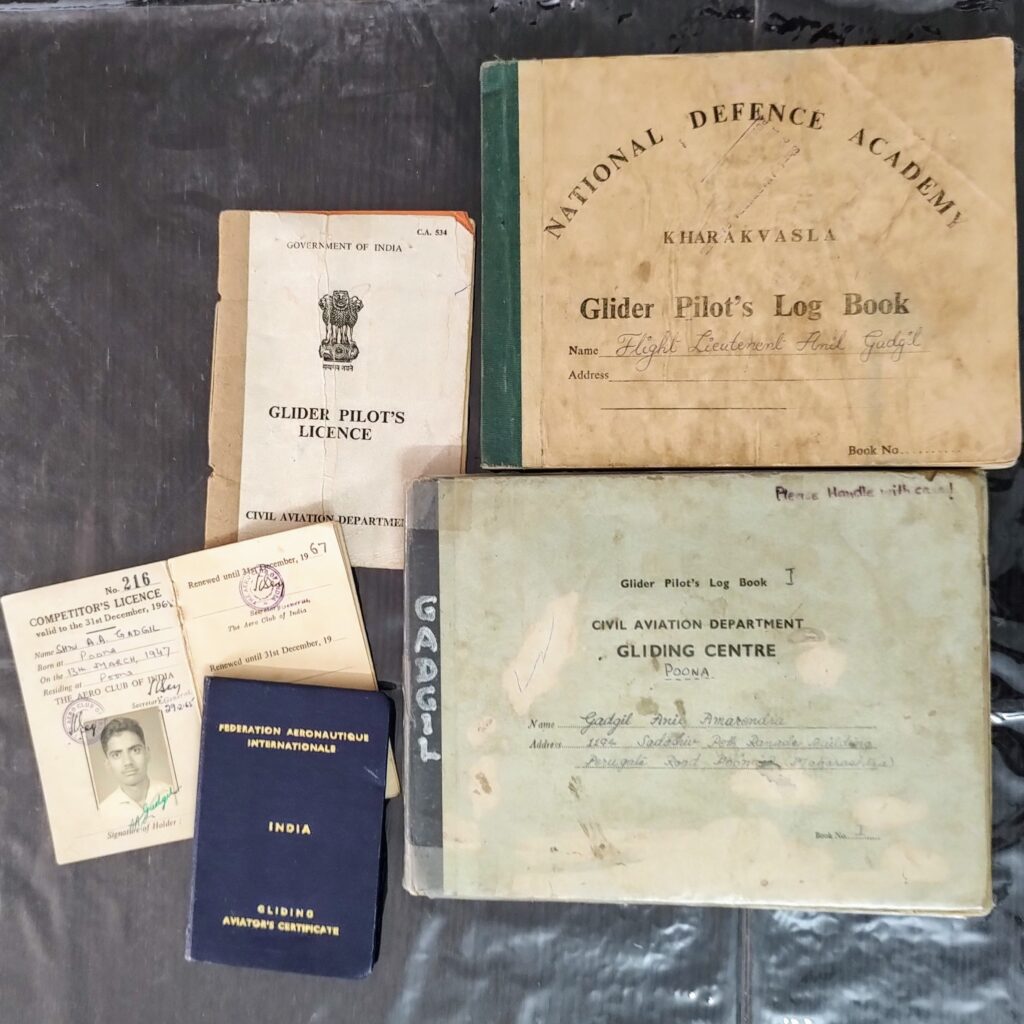

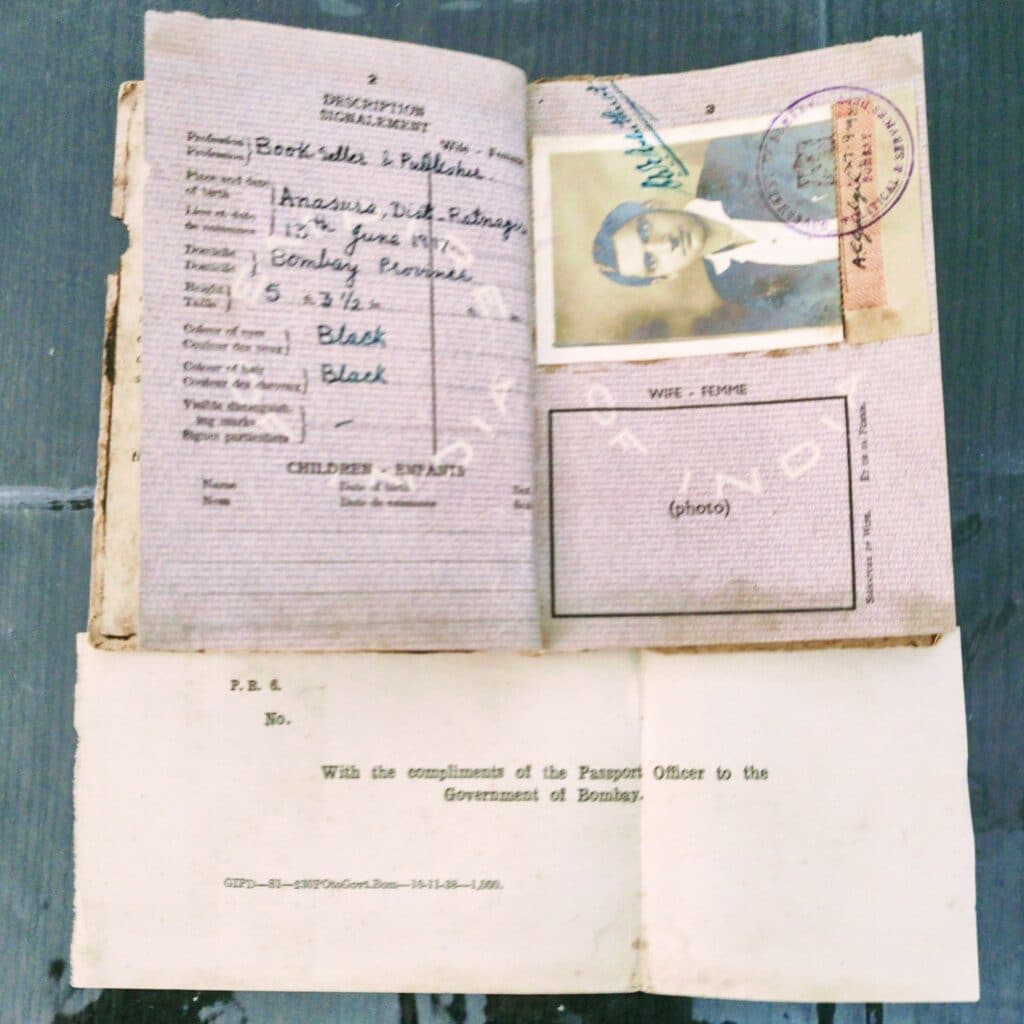

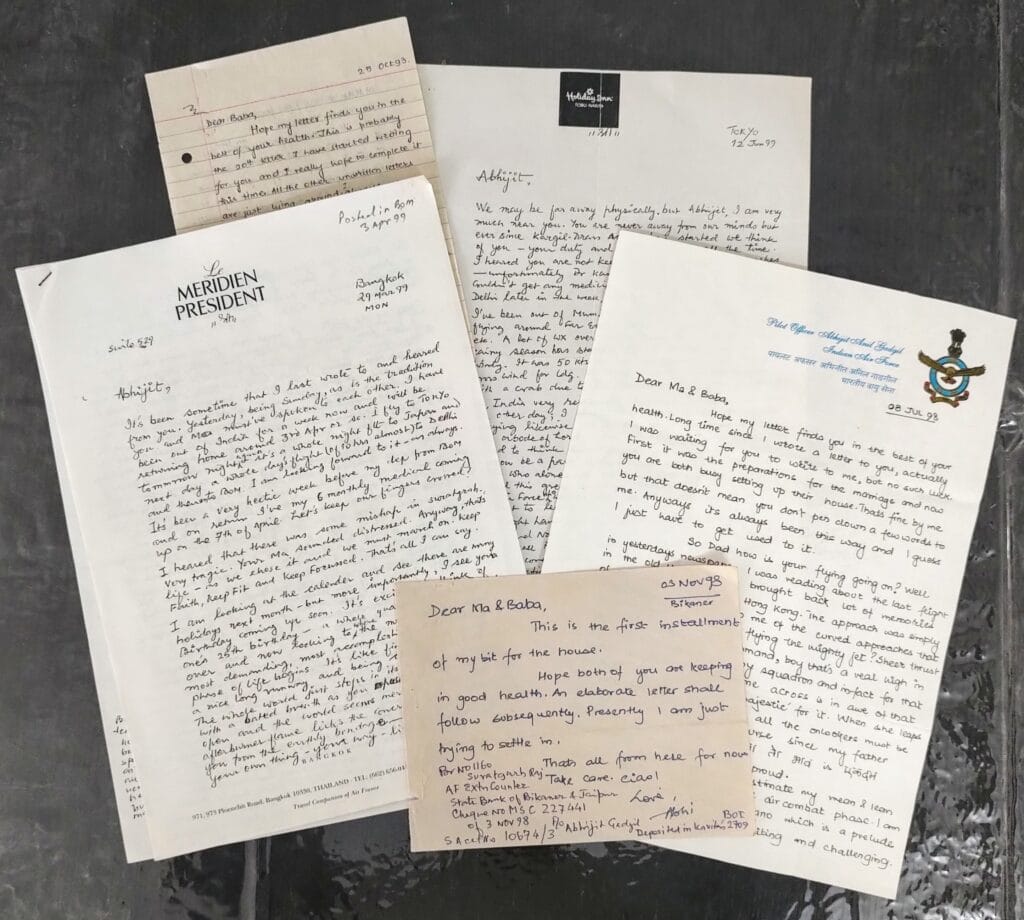

I read Baba’s letters to his mother, talking of mundane things but so full of love, and I read his official correspondence with his DS (Directing Staff, i.e., professor) at the Defence Services Staff College, crisp and professional. I went through his logbooks and saw his solo, and I read his resignation letter telling the MD how he needs to dedicate his time to fighting for Abhi’s cause. I ran into his gliding adventures (I did not know he was a competitive glider pilot!), as I did into about 5-odd dozen files in 9 boxes filled with newspaper cuttings about Abhi’s accident and Maa’s fight. I saw my grandfather’s 1945-issued ‘Empire of India’ passport, and glanced through my grandmother’s recounting of her epic journey to Japan, wearing a 9-yard saree and confidently speaking to the Japanese women in kimonos in Marathi, given that neither did they know any other languages than Japanese and neither did she except Marathi. I saw Abhijit’s bar bills and ration cards and the invoice for his ‘Royal Enfield Bullet 350cc Red’. I saw his flying logbooks and his cap and medals. I started to read but quickly stopped and discarded the letters written to him by his lovers and his notes in the margins. I opened his diaries one by one to see his beautiful handwriting chronicling every day in detail, pages and pages full of mundane and (in hindsight) life-changing things written down as they happened (he diligently maintained a daily diary from 1989 till the day previous to his flaming end; I read his half-written entry on 17 September 2001, the night he took off never to land, but I won’t tell you what it was about). I saw letters my maternal grandfather had written my mother, and how lovingly he called her by 3 pet names because he could not make up his mind on which one he liked the most. I read letters written by my father to his, and me to my father (and him to me), and remembered Kymaia’s daily emails to me. Indeed, I saw a glimpse of my grandparent’s past, their life, my parents’ childhood, their youth, their careers, my brother’s entire life, and my own past. It passed in front of my eyes. In slow motion.

And it felt like dying.

The 3 days I spent clearing this has aged me by 3 years. I have not cried so much nor been so emotionally drained at the end of it as I have over these 3 days. I struggled with myself, wanting to keep every little piece of paper, medal, passport, flying license, letter, wallet, uniform, logbook, diary, photo, and greeting card. But I knew I had to let go. You see, this, my past, including my ancestors and their past, had taken up over 60% of my home. And this was as literally true as it was figuratively. I had no choice but to jettison it. It was too heavy a baggage to carry. And my shoulders are too frail and too weak to lug it and not feel the strain.

I remembered a lesson from, who else, my Baba (who, even though I am 50 this year and he passed away at 72 in 2019, I consider my hero and a superman, a phase from which most kids grow out of by the time they hit teenage) who said:

‘You see, Jumbo, when you are trying to fly, there is this struggle between thrust and drag, between lift and gravity, between your will to fly and your inertia to let things be. The only way to get off the ground is to jettison the baggage you are carrying, lighten the load, release the brakes, open the throttle, and most importantly, keep your eyes focused in front. You can’t want to stay on the ground and soar in the sky. You got to choose. If you are ever stuck wanting to take off but unable to, take a good look at the weight you are carrying and chances are, you’ll find that your greed, your selfishness, and your fear not to let go of things that are comforting to you, especially your past, will be seen as contributing the most to that inability to unstick. So, eyes firmly ahead, release brake, open throttle, and at V1, gently ease that column toward you, my son. May you fly. And may you land on your feet every single time.’

So, I gathered my resolve, held my nerve, and discarded it all (except for the books, which I can never abandon, and the photos, which I asked Vikas to pack and burn without showing, or indeed telling me, for I am not built for that kind of emotional upheaval), albeit one by one, reading every single piece of paper, touching every single piece of possession, living that moment with whoever was connected to it, and then, lovingly setting it down in the pile of scrap that would be burnt or sold.

Frankly, as I see it: by holding it, feeling it, reading it, and imagining myself to be there in that moment with that person, I had separated that paper from the emotions attached to it. I had freed that thing.

As I think I had freed myself and lightened my weight, hopefully by enough to let me take off once again into the blue yonder.

Happy landings, everyone. My new life starts today.

P.S: The following photographs are in no particular order.

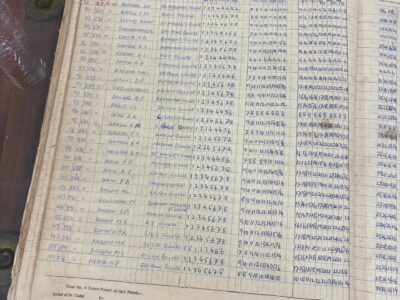

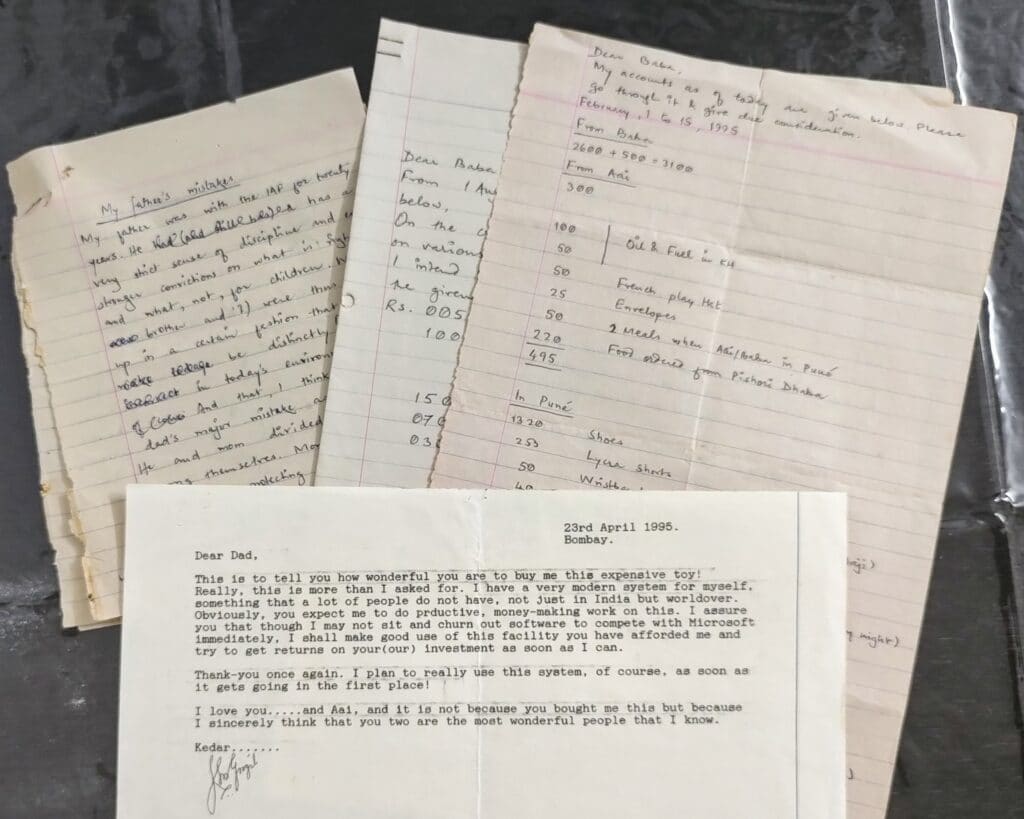

Abhi’s training notes.

All the passports we used to learn to fly.

Baba sent me a gold Visa card when I was 16.

Baba was an avid follower of space travel.

Baba wrote a poem for me when I was born, and then one for Abhi when he was.

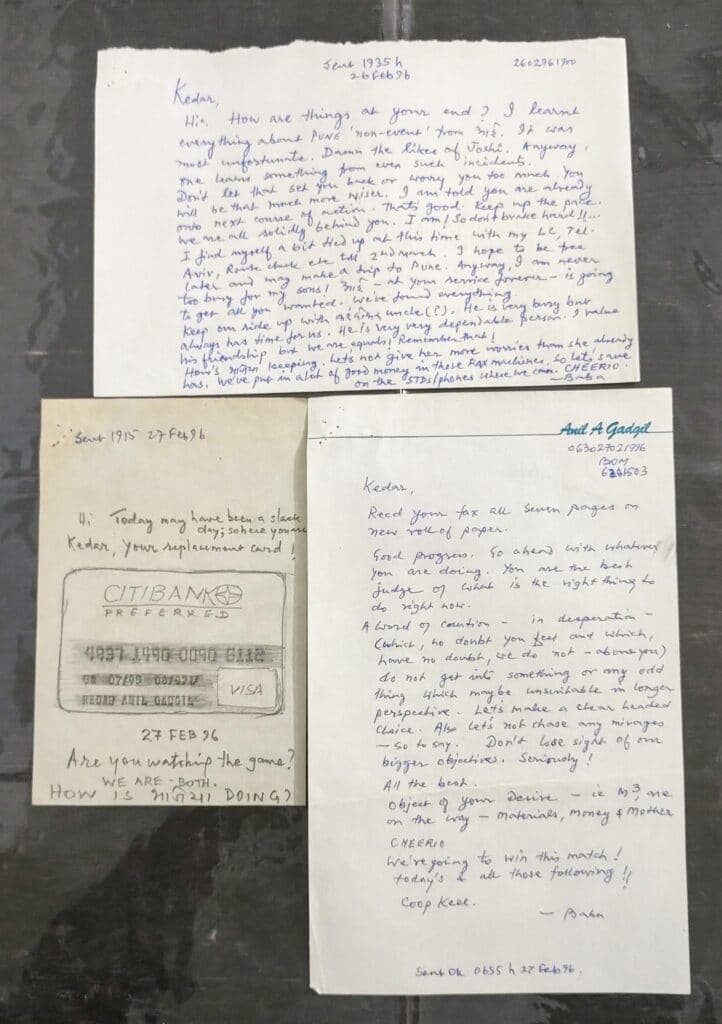

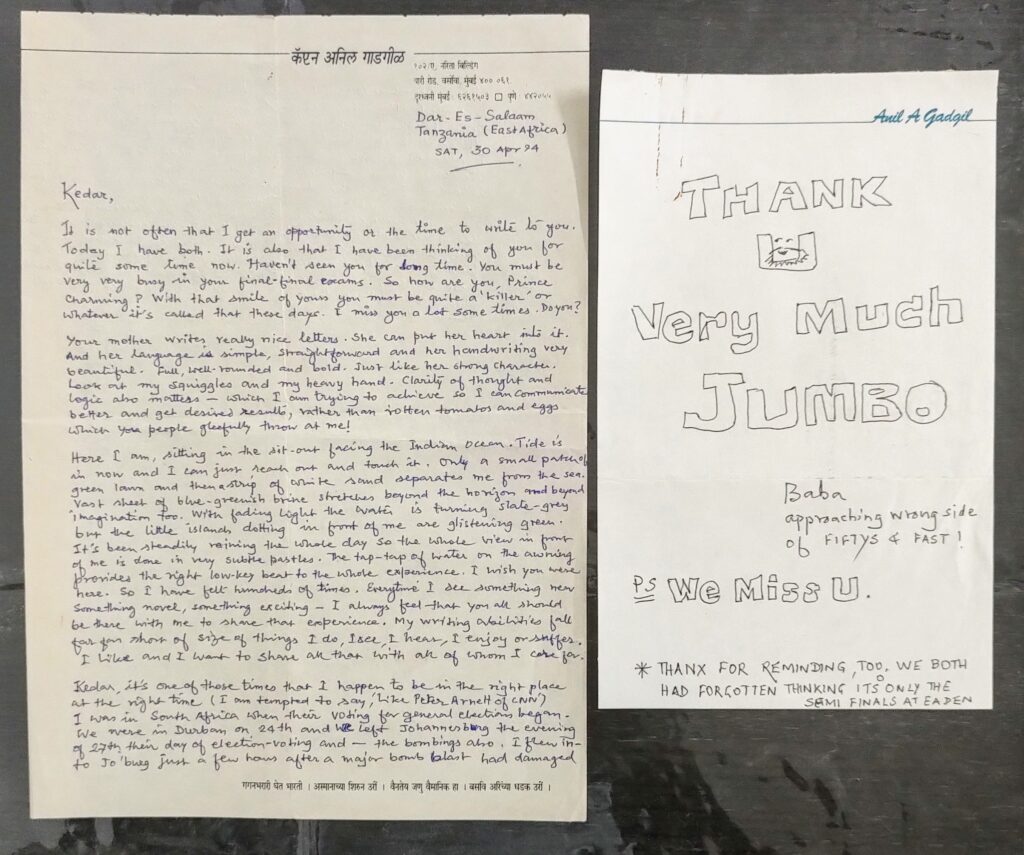

Baba’s letters to me.

Some of my letters to Baba.

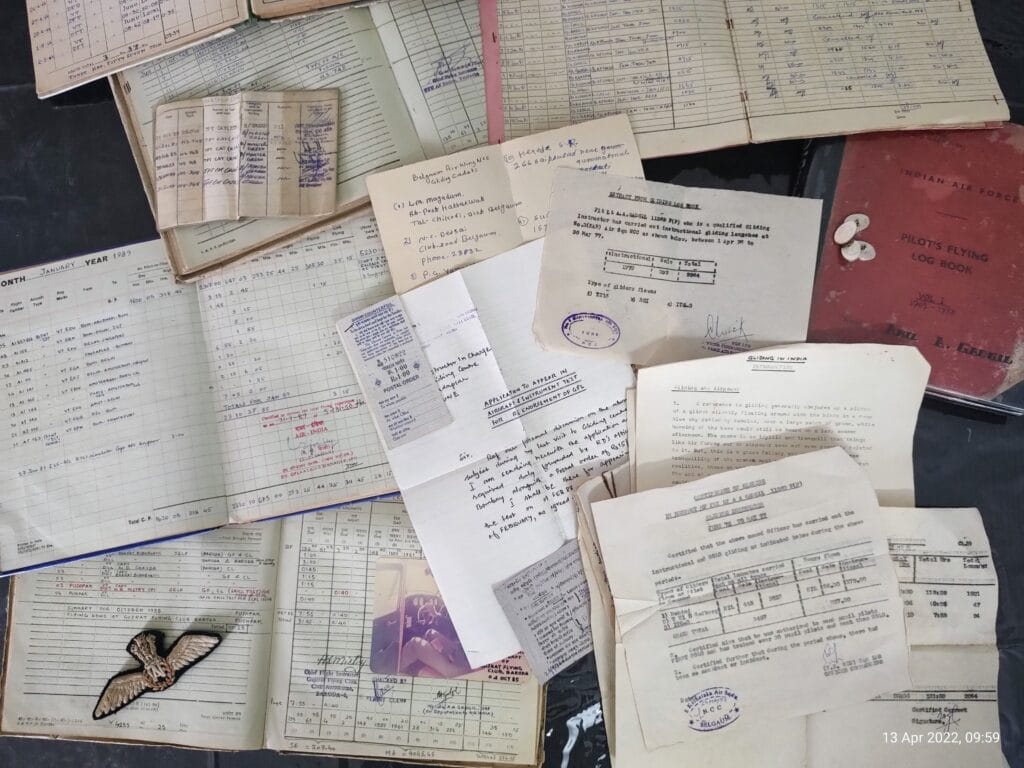

Baba’s logbooks and some related papers.

Baba’s logbooks.

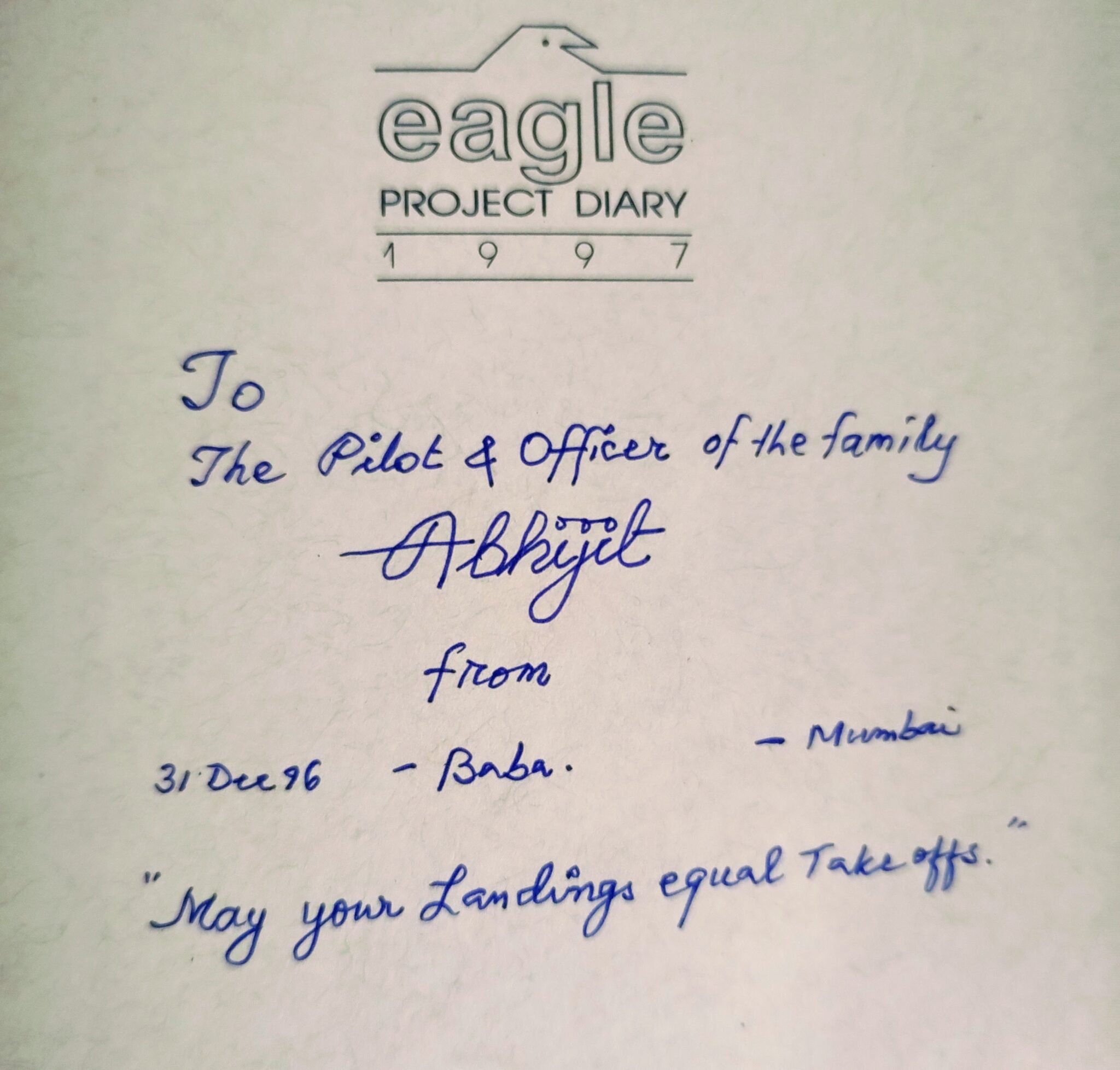

Baba’s wish, other than we be gentlemen, was that our landings always equal our takeoffs.

Cameras and tripods that have captured 1000s of photographs of this family.

Did you notice that the licence numbers are in 2 or 3 digits?

‘Empire of India’ passport.

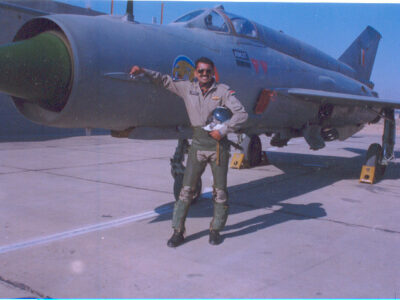

‘First off the ground and the last to touch down.’

‘Flying machine problem solved by Ohio man’ and ‘Everest conquered’.

Going off to a dear friend for his office and warehouse.

I could start a workshop with those tools. But I gave it away to someone who runs a kickass workshop.

I dare not open those trunks with photographs.

I did not know Baba was a competitive glider pilot.

Souvenirs from travels.

The back of my grandfather’s passport from 1945.

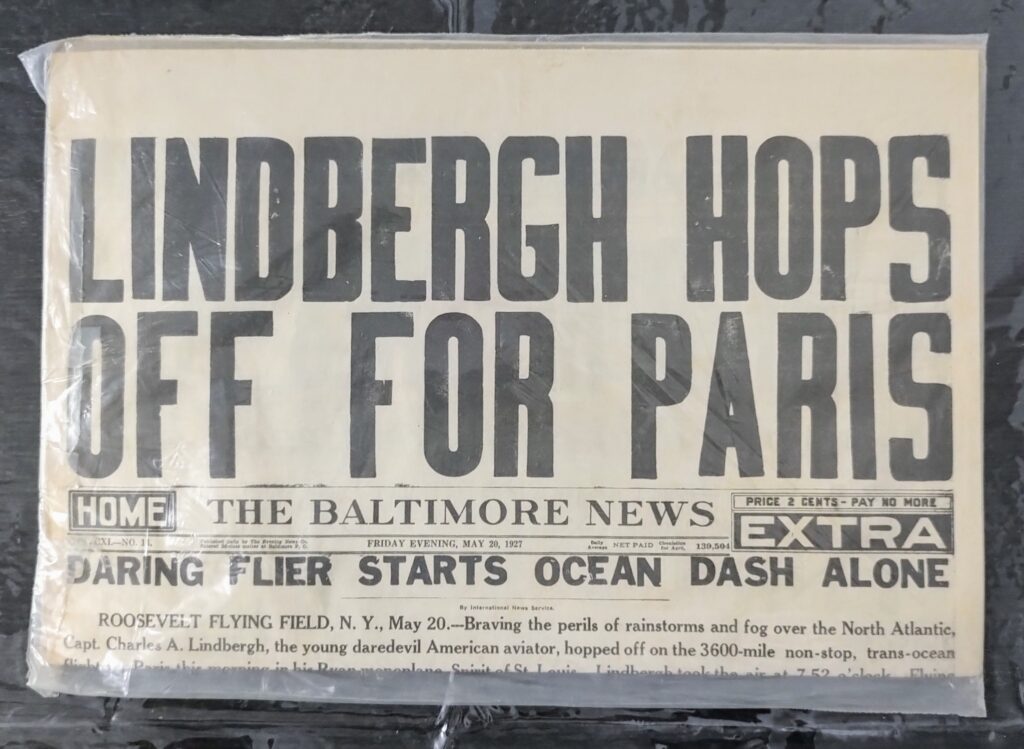

The Baltimore News, 20 May 1927.

The camcorder that recorded our festivals and celebrations.

Apparently, in 1945, the passport officer would send a personal note with your passport, congratulating you for getting a rare document!

Stationary stationery. And these are only the marker pens.

To the scrap buyer, we go.

Abhi’s letter to ACM La Fontaine, expressing his desire to join the IAF.

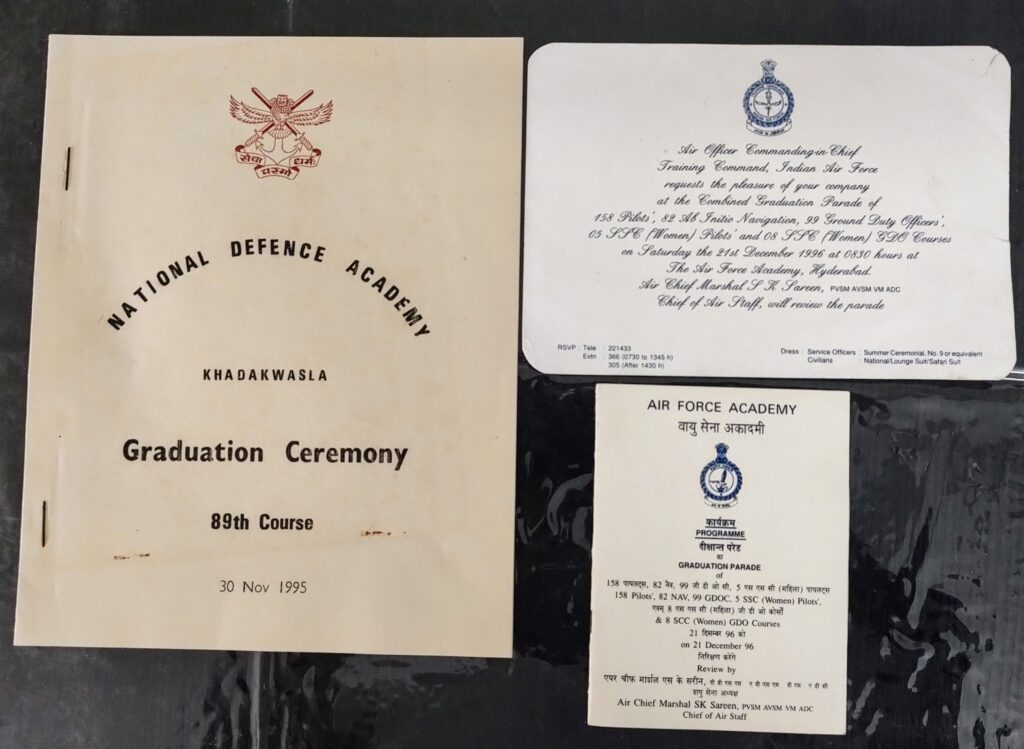

Abhi made it to the NDA and later to the AFA, becoming a commissioned officer in the IAF.

A very small part of the vast correspondence between Baba and Abhi. Note Baba’s concern for flight safety in Suratgarh.

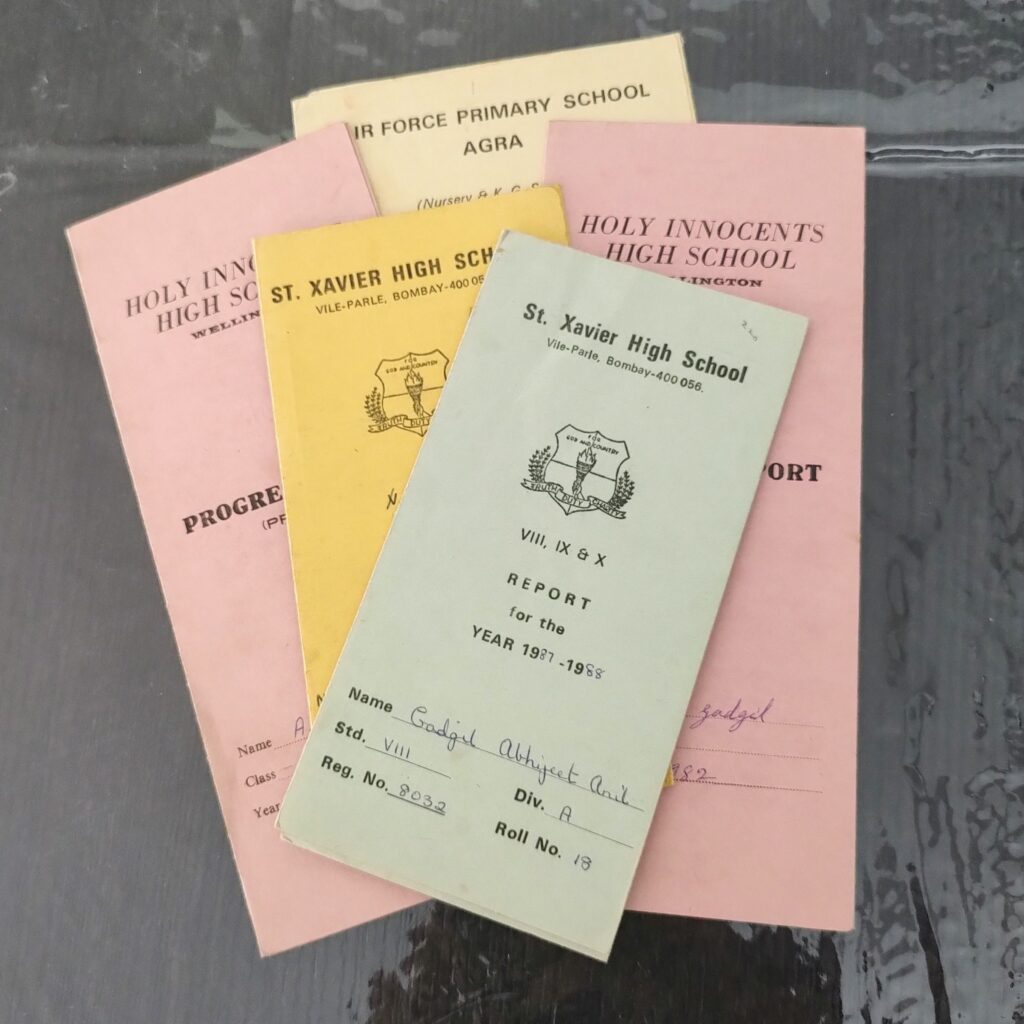

Abhi’s reports cards. Don’t ask me the scores inside. He never let his schooling interfere in his education.

Our cards to Baba on his professional anniversary in 1987 and 1988.

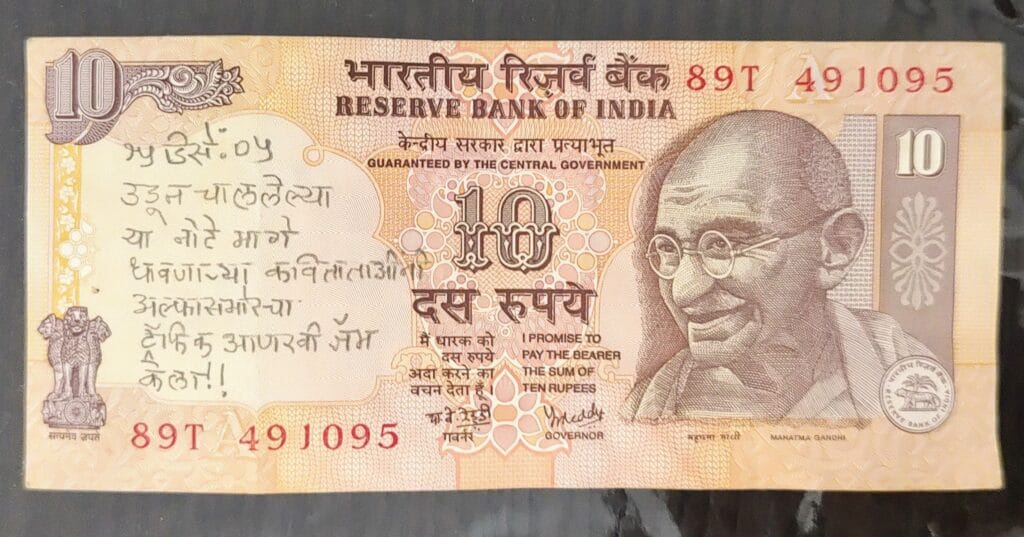

Maa ran behind this Rs.10 note in front of Alpha Supermarket in Andheri Mumbai on 15 Dec 2005. And Baba, in his beautiful handwriting and delightful flair for humour, wrote this romantic note and gifted the note to Maa.

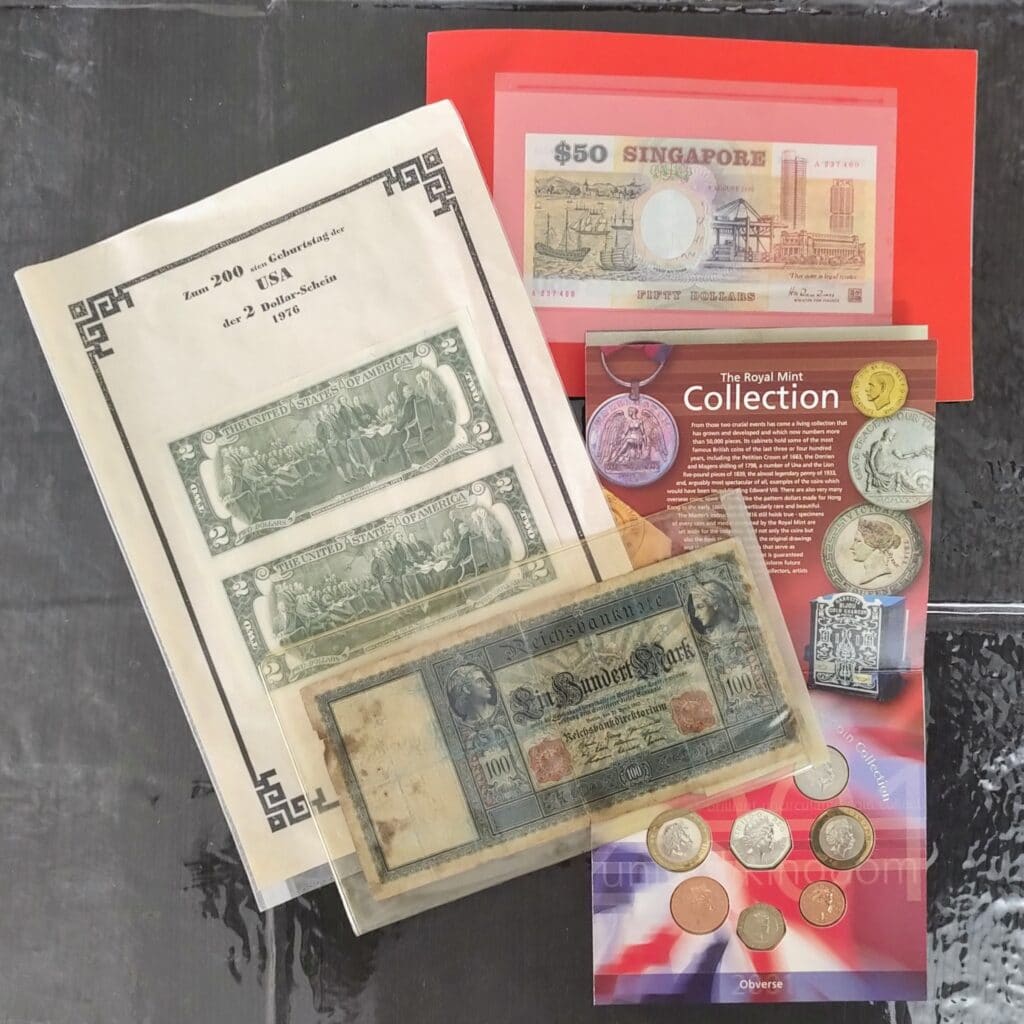

Some of Baba’s collections. I never thought he had any hobbies other than flying and teaching about flying. Just goes to show how little we know our own people!

The remains of Abhi’s two wallets. Some of these currencies are extinct now.

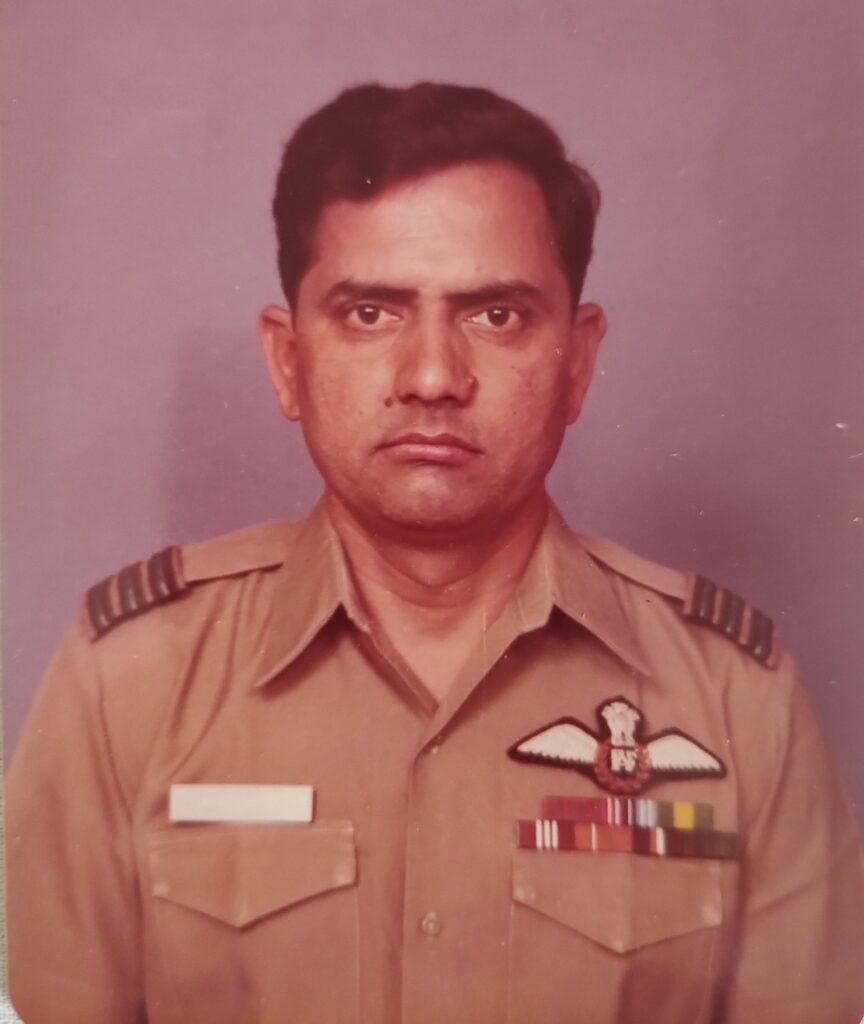

Baba in his Wg Cdr’s khaki uniform.

Baba’s old khaki uniform with Wg Cdr’s rank.

MiG21 cockpit controls from the aircraft we had at Kavita Farms – Top view.

MiG21 cockpit controls from the aircraft we had at Kavita Farms.

Photograph of the Iskra cockpit with Abhi’s hand holding the joystick.