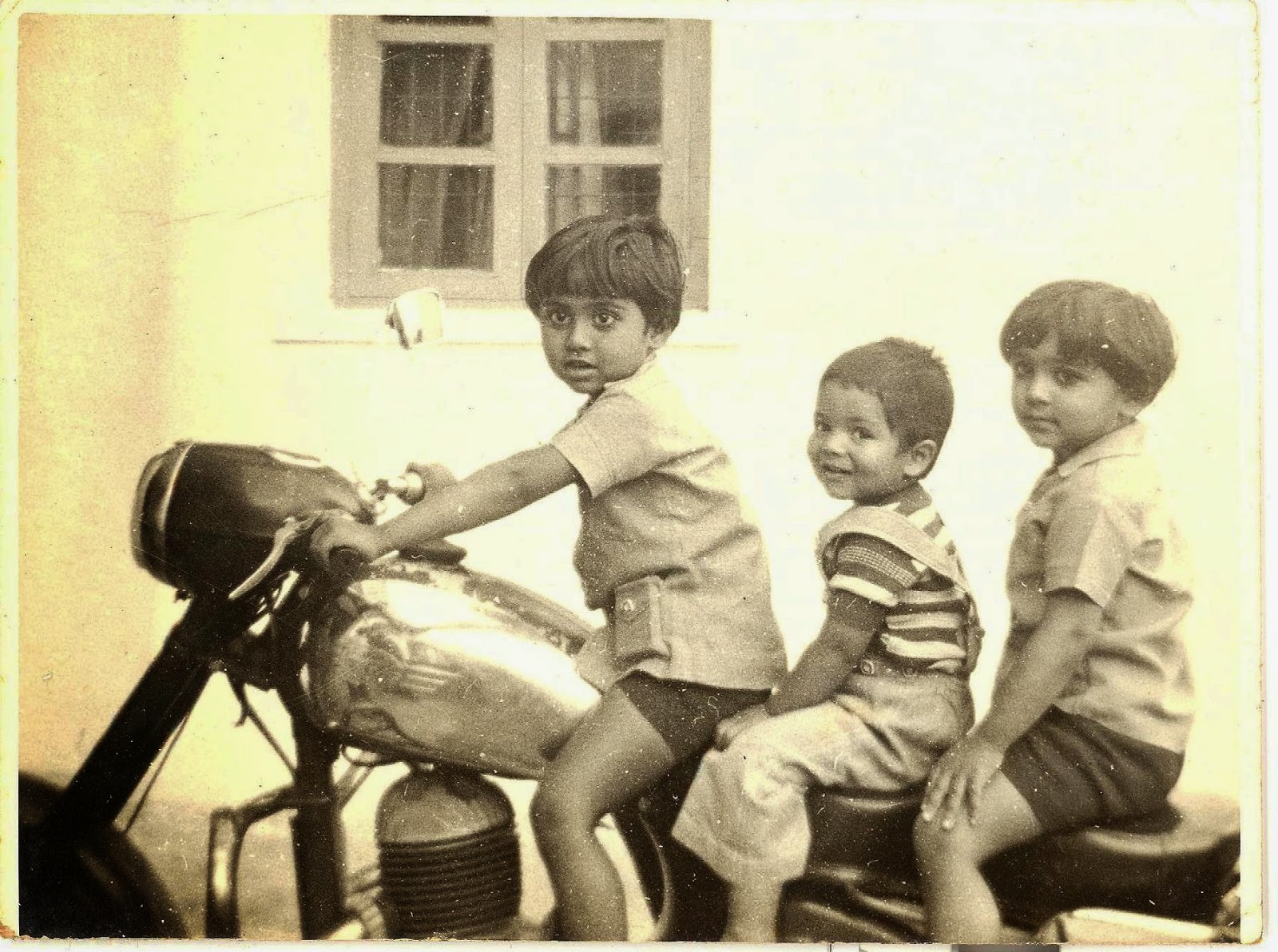

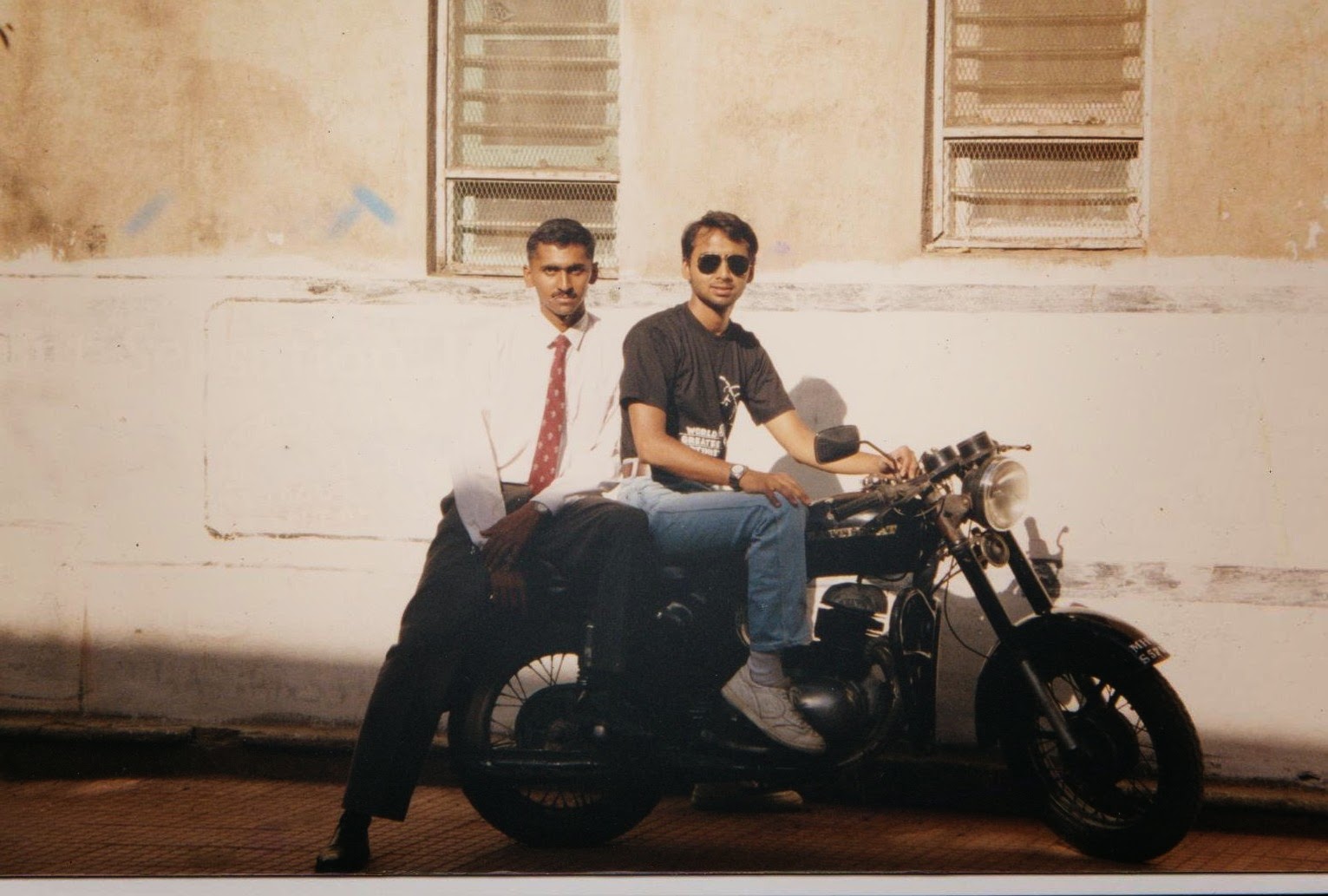

The Gadgil brothers and the Manerikar scion. Like father, like son(s).

O! The sweet memories of youthful glow

The sound of the throaty purring

Of my sweetheart in full flow

Wind in my hair, my soul calm, unstirringMe caressing her, gently guiding the majestic frame

Flying through the air, the world but ours to claim

She pushed all my buttons, as I think I pushed hers

It was with her, and on her that I truly earned my spursTake me back to that time, oh my heart bleeds

Bring back those lovely, heady days

When boys were boys, and steeds were steeds!

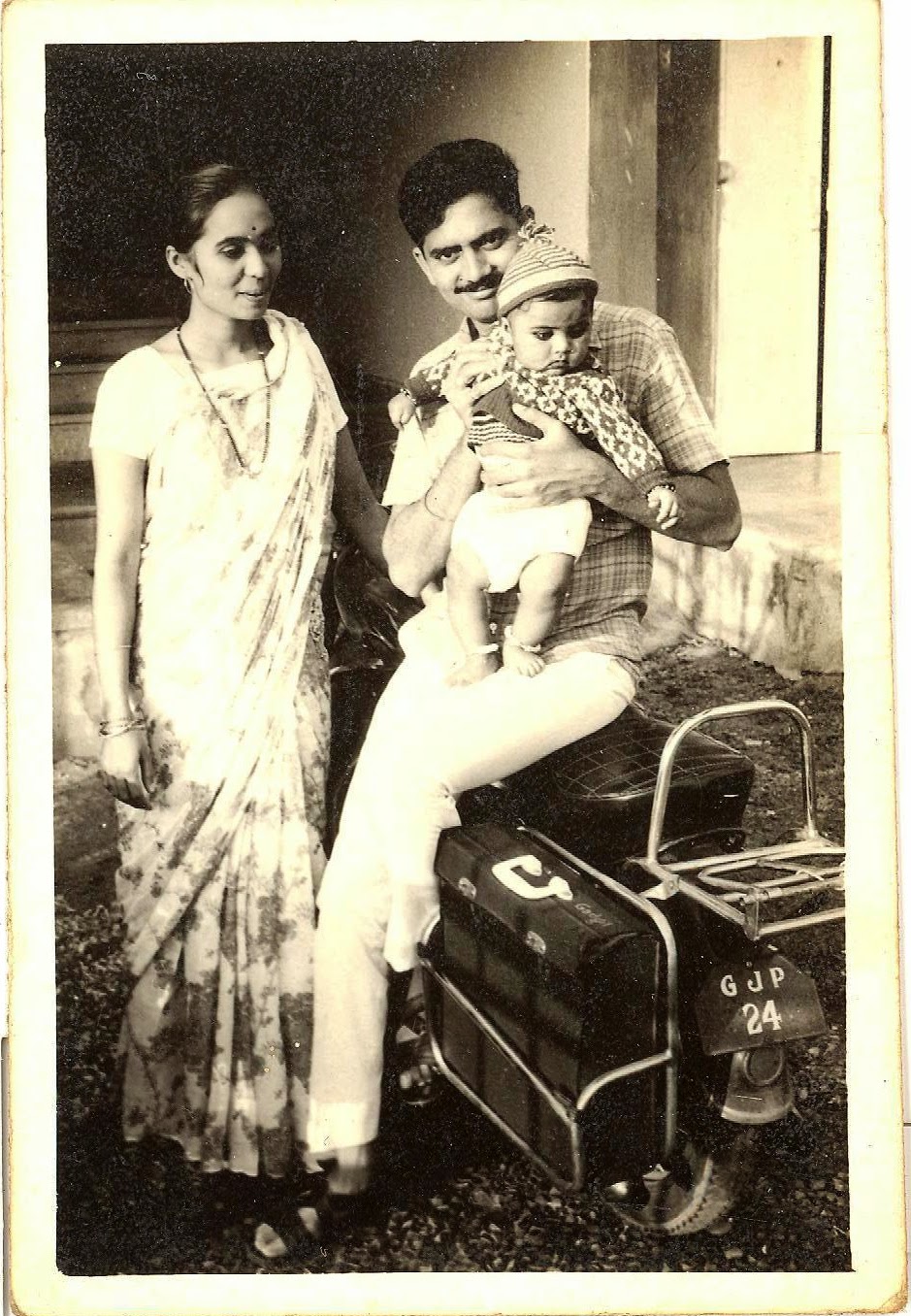

Back in 1969, my father (along with 6 other brother officers) was given a loan of Rs.2,000 by the Air Force, to buy a motorcycle. The 7 gentlemen (posted in Jamnagar) went to the motorcycle shop (I don’t think there were company showrooms then, since there was also an Enfield Bullet in there then) and ordered 7 Jawas, all bottle-green (though, by the time I saw the bike, I always thought it was black, for some reason), for a princely sum of Rs.4,500 each. On the day of the delivery, they found a Parsi gentleman who had bought the bullet (for Rs.6,500, if I am not mistaken, as per Baba) there and had come to take the delivery himself. He took the bike out, and proceeded, almost immediately, to skid and fall. The bike and the rider were both unhurt, but he took it as a bad omen, and came back to the shop wanting to sell his brand new bike for Rs.6,000! Of course, needless to say, none of the young officers had that kind of money, and they ended up picking up their 7 Jawas, and riding out. The bikes were numbered GJP 20 to 26, and Baba’s bike was GJP 24.

Maa, Baba, and I with the Battlecat.

As soon as they were out of the shop, they decided to ride to Delhi (don’t ask!). This is even more surprising, not just because the bikes those days had to be ‘run in’, but also because none of them had a driver’s licence (though they were all pilots and could fly planes!) or knew how to even change a spark plug, which was an essential skill to ride bikes then. But of they went. Somewhere just outside the city, it began to rain, and there was an oil slick on the road. these flyboys, riding (in a straight line) as if there was no tomorrow, probably did not know what it can do. So, when the first rider slipped and went skidding, the others (even before they began to laugh) started to do the same, and there was a 7-bike pile-up, with the egos more bruised than the bodies and machines! To cut a long story short, they returned to the squadron with their tail between their legs, and tall stories to tell to avoid any mention of their first failed trip (there were many successful ones later, but not this one, regardless of what the 1969 batch IAF Jamnagar chaps tell you. Take it from me).

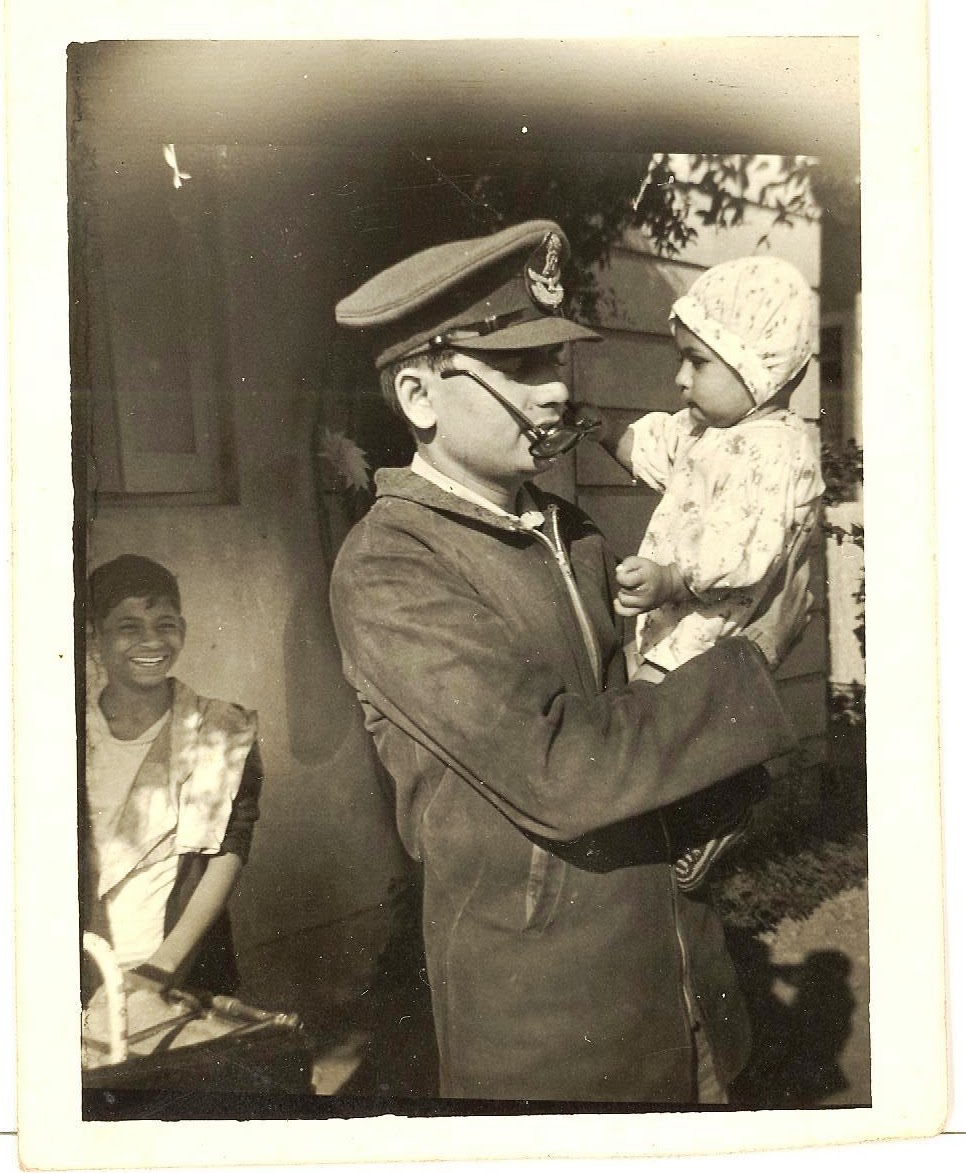

Some years later, when there was a ‘computer exhibition’ in Delhi (where Baba was based by that time), the only thing they knew was that there are pretty girls in sarees at the counters (real personal computers were at least two decades away), and Baba and his friend (the late Manerikar uncle) took his (Baba’s) Jawa and went to see it. After spotting a pretty girl who seemed amenable to being approached by two officers in uniform (no prizes for guessing why they went in their khakis, which was what the IAF uniforms were before they turned blue!), Moony uncle screwed up the courage to talk to her and ask her to come out for a Coke after the exhibition. While the girl was finishing her duties, Moony uncle pleaded with Baba to give him the bike and walk back to the squadron, and gallant as he was, he did it for a friend. Anyway, the next day, they went again, and once again, Moony uncle asked the same girl to come out. Baba, by this time losing patience, intervened and informed her (and you have to imagine this in his then very Marathi-accented English, spoken with trepidation though righteously indignant voice) that the bike was, in fact, his! To cut a long story short, she didn’t take the offer!

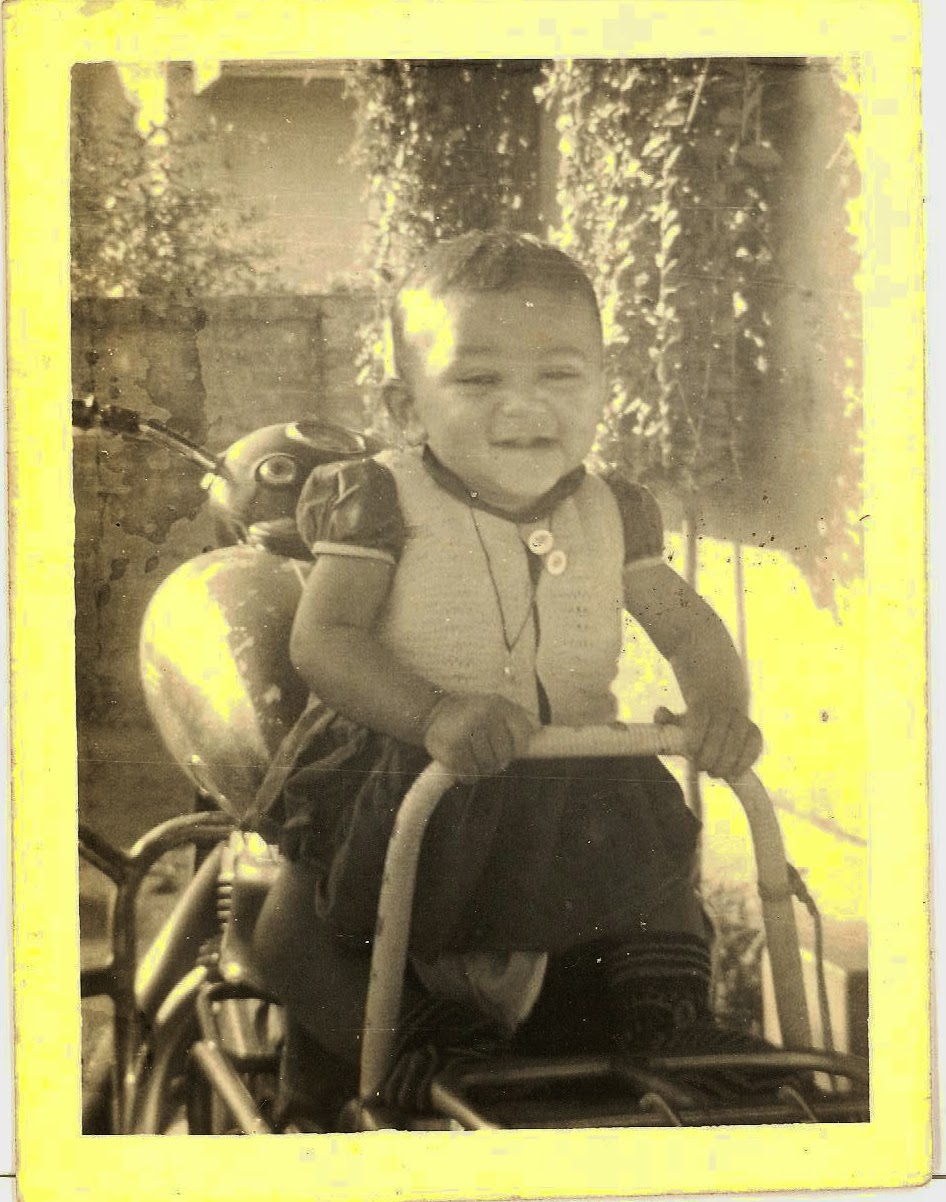

Abhi with the Battlecat. She’s seen us grow!

Later, when baba was courting my Maa (then his girlfriend) who was working in the Bank of Maharashtra at Bajirao Road in Pune, and he was stationed in Delhi, he had a kind CO who would ask for him if a Dakota (Baba’s favourite aircraft, even after flying the 747 for half his life!) had to be ferried to Nasik for repairs, and would tell him, ‘Gads, I believe you have a pretty lady in Pune? Why don’t you load your bike in the aircraft and go to Nasik for a week?’ (well, the Air Force was different then, and far more indulgent, with COs having far more power than they can dare to imagine today). So, he would come to Nasik, unload the Jawa and ride to Pune (because the CO wrote him a note that the ‘mess food was bad in Nasik and the officers were entitled accommodations in Pune’), and wait outside her house or her bank, for her to come out. Eventually, they got married in 1971, and that was 42 happy years ago (the story of how he impressed her by turning up cheekily in his uniform for a matinee show of Aradhana and then proposed to her in a glider is the stuff of family legends, though this post is about the bike. So, some other time).

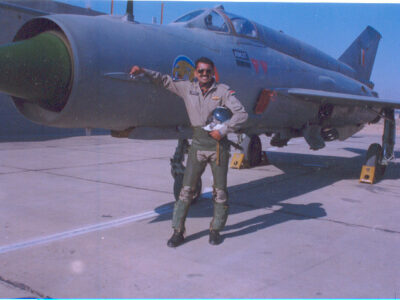

An officer & the gentlemen.

Throughout our childhood, the Jawa was a constant companion. The four of us on that bike, with me sitting on the tank, imagining that I was steering her, the wind in my hair, singing loudly (I have not lost that habit yet, and the moment I am in a moving vehicle, I tend to sing), Baba’s chest as my backrest, and Maa sitting sideways as pillion, holding the infant Abhi in her arms, wedged between her and Baba (did we realise how dangerous that was? I don’t know. We probably knew of no other way to travel), we did numerous trips from the Air Force camp to the nearest markets, to the mess, to the cinema, to the clubs, to the railway station, to my parents’ friends’ houses. We went everywhere on that bike. The sound of the metallic ‘phut-phut’ will never leave my memories, regardless of which other transportation I use, and regardless of how sophisticated and cutting-edge the technology is. The Jawa, her sound, her feel, her looks, and her touch will never leave me till my last breath.

In 1988, when I turned 16, he asked me to take the bike. I was surprised, to put it mildly, till I realised that he did not mean the bike AND the key to it: just the bike. I was to practice putting her on the stand, taking her off, walking with her on the right, and on the left, leaning with her on my left and on my right to feel and be comfortable with her weight, and to sit on the saddle and use my legs to push and then balance her. Basically, as he put it, ‘Let the machine be an extension of your body’. And boy, was it boring! But it has made me a good rider, and saved my life more than once because I knew how she handled instinctively in a situation.

‘The elation of 250cc thumping under your thighs’ was how Abhi used to describe her.

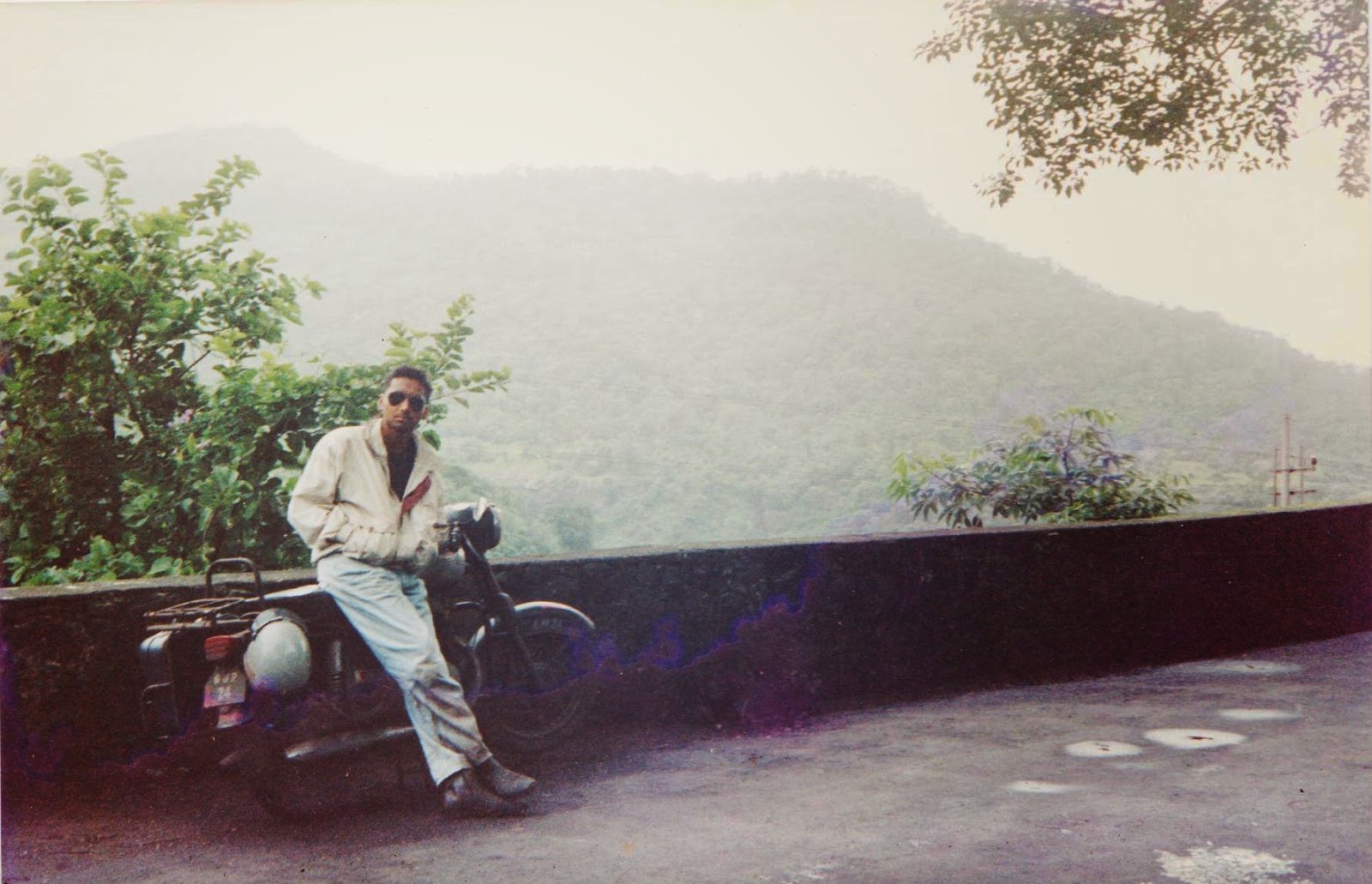

When I came to Pune to study engineering in 1990, he forbade me to take the bike (in any case, he was a stickler for rules and I only got the key to the bike when I showed him my driver’s licence at the age of 18) to another town (we lived in Mumbai then, and he was with Air India by that time). Anyway, since all my friends had shiny, new bikes (Kawasaki Bajaj, Yamaha RX100, and TVS Suzuki were the popular brands then), I felt left out, and one day, when the entire family was in Pune for a function, I sneaked back to Mumbai and drove the bike to Pune (this is, once again, another story, because it was the middle of the monsoon, and the Pune-Mumbai expressway wasn’t even a figment of anyone’s imagination then).

The Battlecat, the long & winding roads of the ghats, rains, Raybans, jacket, boots: A boy’s ultimate dream (before girls come into the picture).

When I arrived, wet, dirty, and a bit scared of the reaction of the seniors (my Maa, my Mama, Mami, Grandma, and of course, Baba), I was given a thorough dressing down by everyone, which I was prepared for. But when Baba told the gathering that he is going to have a ‘talk’ with me outside, I was almost wetting my pants, as we walked out in the garden where the bike was. He was silent while he looked at her, touched her, and turned to me to talk, and I shall remember this till my last breath: ‘Son, I am proud of you. That, what you did, takes guts. You are a bloody star! And when we go inside, you are to behave as if suitably chastised, and I shall behave suitably indignant. Deal?’ And then, he hugged me.

(Later edit: Just. Wow. If I ever catch my daughter doing this, I have no clue how I’ll react, and can only hope I have the sang froid my dad showed that day).

Before we went in though, gave me some advice that was ostensibly about the bike, but methinks it was deeper than that. Pardon my French, but I must reproduce it here verbatim: ‘OK, now that you have taken her from me, let me tell you something that will stand you in good stead. Listen to her like she is a living being. You can tell almost anything by just learning to listen to your machine. And yes, treat her like your wife, and she will treat you like a lover; treat her like a whore, and she’ll fuck you when you least expect it’. I have taken this advice to heart about most things I have, and with excellent results. Thank you, Baba. As I always say, if I can be half the man you have been, and continue to be, I shall consider myself a success.

In later years, I learnt to strip the Battlecat bare and put her together (not really blindfolded, but almost). She was one of the (no, correction: she was THE) most beautiful machines I have ever had the pleasure to operate. Everything (except the starting capacitor) was mechanical and it was just so elegantly designed. One could ride her without the clutch cable (which in those days, had a nasty habit of snapping just at the wrong time!). The design had the most comfortable riding posture I have ever seen on a bike, and I think I looked pretty good just riding her through Pune roads.

The later avtaar of the Battlecat, with a new headlamp, handles, and seat (note that the Rayban is unchanged).

The kick/gear combination was forever a conversation starter, and I have lost count of the number of ladies I have impressed with the claim of ‘250cc per cylinder’ (no one ever asked me how many cylinders. Just one, for those who want to know). I even bought and stuck (M-Seal zindabad) brass letters that said B-A-T-T-L-E-C-A-T on both sides of the tank, and was used to polishing them with Brasso (you had to cover the rest of the tank with newspaper because it would mess with the paint otherwise) every day for a shiny look.

In 2005, alas, I do not know what overcame me, but I sold her to a mechanic in Mumbai for a paltry Rs.5,000, by which time she had become a rust-bucket. Both Baba and I felt sad seeing her go, but I like to think of all the great memories I have had of her and with her that only she and I are privy to, and how I would never exchange those for all the gold in the world. The details, of course, shall forever remain our secret.

My Battlecat, wherever you are, remember that I miss you.