There is something almost poetic about the parallels between the rather animated discourse around the Prime Minister’s academic credentials and the Indian Air Force’s losses during the recent military skirmish with Pakistan. Both, it seems, are not to be questioned. At least, that is the implicit directive issued by the self-anointed custodians of patriotism on the right, whose reflexive instinct is to treat scrutiny as sedition. Equally, the performative left, in its bid to lampoon anything that breathes within a ten-mile radius of the government, ridicules both: the supposed absence of a degree, and the aircraft that fell. Neither camp, I dare say, emerges with dignity intact.

Let us begin by addressing the proverbial elephant in the room. Whether or not the Prime Minister possesses a degree is of little consequence in a functional democracy. One does not require a framed certificate to possess wisdom, nor does the absence of academic letters preclude statesmanship. History is replete with examples of monarchs, revolutionaries, and nation-builders who may not have passed examinations, but who have passed into memory for all the right reasons. Similarly, it would be intellectually dishonest to suggest that a modern democracy like India is incapable of electing a leader based on qualities other than formal education. The Constitution does not demand it. Neither should we.

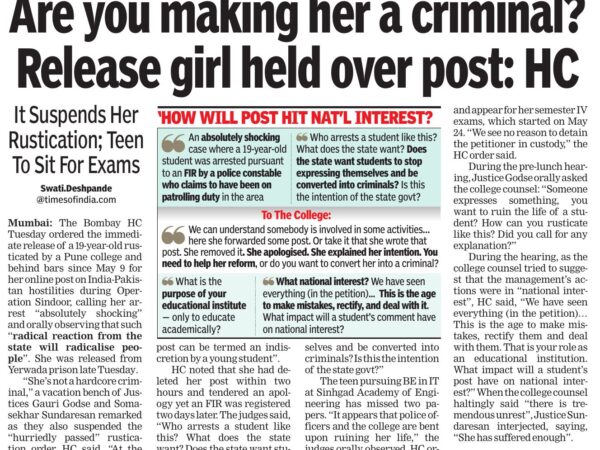

And yet, what rankles is not the absence of the degree, but the compulsive need to fabricate, to conceal, to obfuscate. The sin is not one of omission, but of deception. If indeed the Prime Minister was too immersed in political activity, or social work, or existential contemplation to complete a university course, that is not an indictment. It is a biographical detail. The crime lies not in the truth, but in the lies we are asked to digest in its place. Why must the public be treated as children in need of bedtime fables? Why is transparency such an alien virtue to those who derive their legitimacy from the people’s mandate?

The same obfuscation rears its head when we examine the discourse around military losses. War is, by its nature, ruinous. Men die. Machines fall. Debts rise. There has never been a war in which both sides do not limp away with wounds. To pretend otherwise is to insult the intelligence of a citizenry that has endured the blood-stained arithmetic of Partition, the breathless tension of Kargil, and the long shadow of insurgency. It is precisely because we know the cost that we ask the questions. And to refuse answers, to belittle those who ask, is to infantilise the public while simultaneously dishonouring the military itself.

Indeed, it is a peculiar kind of patriotism that seeks to shield the armed forces from scrutiny by suggesting they are too fragile to handle it. That the morale of battle-hardened soldiers would collapse if their losses were reported honestly seems not only absurd, but deeply disrespectful to their courage. It also assumes that the citizens who fund these wars, whose children man those borders, and whose lives are shaped by the outcomes, are incapable of understanding the cost. If that is the standard of democracy we are to inherit, then we are not citizens. We are spectators at a heavily curated pageant, applauding on cue.

This brings us to the final and most specious argument: that one must not question such matters while the metaphorical (or literal) cannons are still warm. That silence, even if temporary, is the price of patriotism. To which one must respond with a short walk down the annals of Indian parliamentary history.

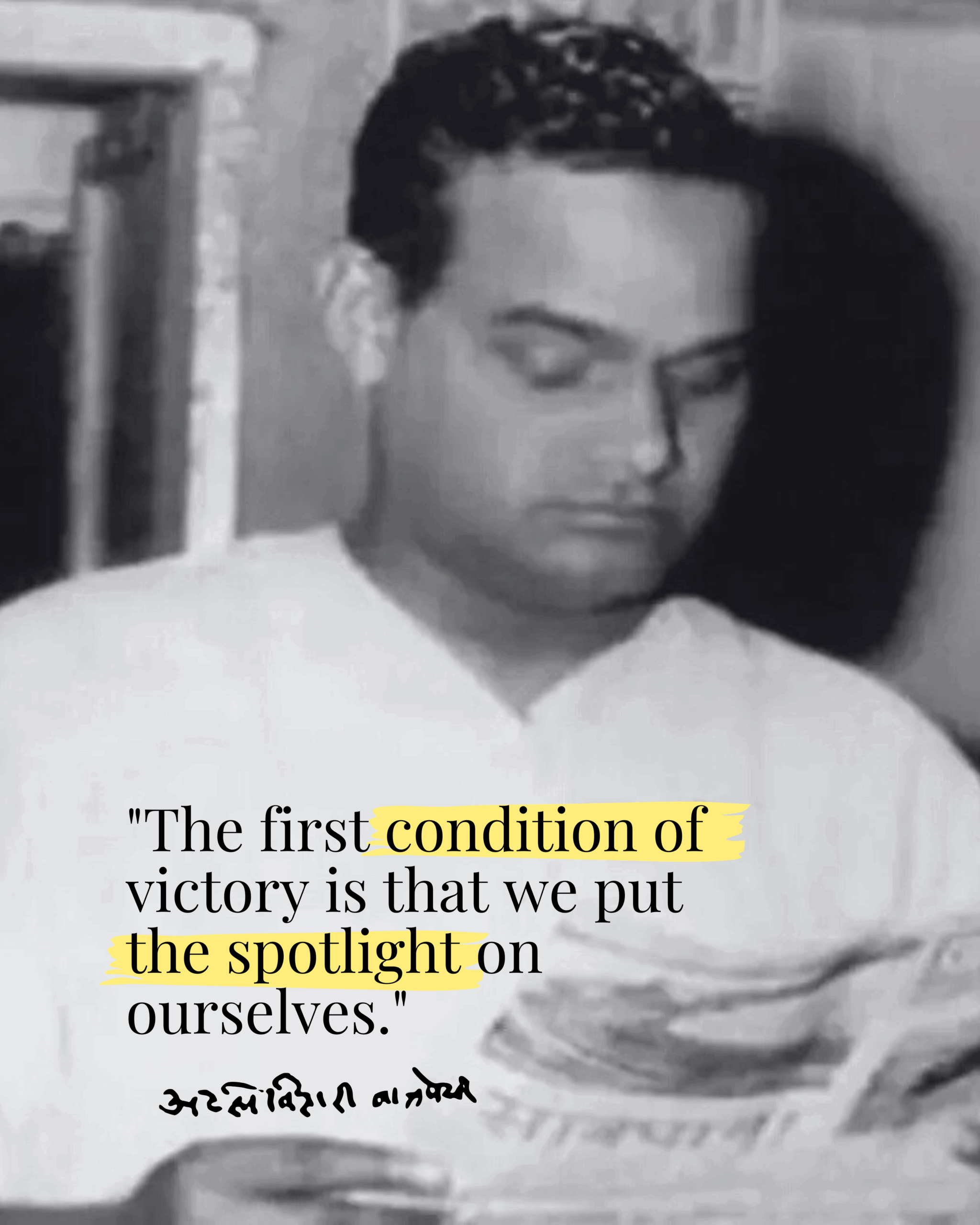

In the midst of the 1962 war, when Chinese troops had crossed the Himalayas and all seemed lost, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, then just 36, a young opposition MP from Jan Sangh, with a mere 14 seats in the Parliament, demanded a debate in Parliament. And Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of independent India, 72 years of age and a political colossus with 361 seats (a majority of over 70% in the Lok Sabha), himself no friend of meekness, agreed. Indeed, when it was suggested that the special sitting should be a “secret session”, Nehru, in a show of immense democratic maturity, and a complete absence of insecurity, rejected the suggestion saying the issues before the House are of “high interest to the whole country”.

The Parliament was called. They debated with the nation under siege. Vajpayee tore into the government. Nehru defended vigorously. There was rhetoric and anger, resoluteness and determination, questions and ripostes. And yet somehow, democracy did not collapse. The Himalayas did not crumble. The war, regrettably, was lost. But dignity was not. On either side.

And so, one must ask: are we now to declare Vajpayee an anti-national? Are we to believe that debate is disloyalty? That accountability must wait for the convenience of those in power? Or, and this is the more disturbing possibility, are we simply so numbed by years of manufactured consent that we no longer remember what dissent even sounds like?

I have watched this country lurch through riot and reform, through moral panic and misplaced triumphalism. I have seen tanks and typewriters, slogans and silence, take turns defining what it means to be Indian. And what I know, what I know deeply, is that patriotism is not obedience. It is courage. The courage to ask. The courage to demand truth, even when it is inconvenient. Especially when it is inconvenient.

I do not question my country because I hate it. I question it because I love it too much to let lies become policy. And I will never be told to hush while those in charge confuse their convenience with our loyalty.

That, I am afraid, is non-negotiable.