Maheshwer Peri, in his inimitable fashion, has once again held up a mirror to a startup ecosystem that would much rather gaze into a spotlight. His recent post is less a revelation than a confirmation, for those of us who have been shouting into the void for some time now, that something deeply rotten lies at the heart of Indian venture capital.

Let me be specific. I do not speak of all investors, everywhere. I do not claim universal expertise. I speak only of what I know. And what I know is this: In India, the people who control the capital, the people who write the cheques and nod sagely on panels titled “Building Ethical Businesses at Scale,” have almost no regard for ethics. Or honesty. Or even actual innovation. What they have is a nose for scale, a taste for narrative, and an uncanny ability to develop selective amnesia when the next unicorn sprouts a horn soaked in blood.

But even this much-vaunted nose fails them, again and again. Their field of vision is tragically narrow: upper-caste, urban, male, English-speaking, and institutionally endorsed. As I wrote in “An Innovaful of Deplorables,” this ecosystem is not blind because it lacks eyes. It is blind because it refuses to look beyond its comfort zone.

We are not short on innovation in India. We are short on imagination among those who hold the chequebooks. The ecosystem simply does not know how to recognise brilliance when it comes wrapped in a sari instead of a hoodie, or when it speaks in Marathi or Maithili instead of Americanised pitch-deck English. It cannot see value unless it mirrors the people already sitting at the table. What we get instead is a parade of sameness, founders solving first-world problems for Tier-1 cities while the rest of the country waits outside the building, holding ideas forged in necessity, resilience, and lived experience.

Now, I can already hear the rebuttal: “But we do fund for the underprivileged. We invest in health, education, sustainability, rural finance.”

Perhaps. But funding the probable solutions to the problems of the underprivileged is not the same as funding the underprivileged, leave alone funding the underprivileged to lead. Diversity is not served when the same elite circles simply shift their gaze to the poor. It is not enough to fund solutions for communities if those communities remain locked out of the boardroom. If your idea of inclusion is to give a platform to the privileged who want to ‘uplift’ others, but never to those others themselves, what you are offering is benevolent colonialism dressed in ESG metrics.

More importantly, let us not lose the plot here. The central issue I am raising is not diversity. That is a necessary digression, but the argument here is about integrity. The ethical rot that pervades the funding pipeline. The tacit acceptance of deceit as strategy. The normalisation of red flags as ‘early-stage risks’.

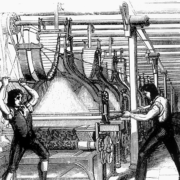

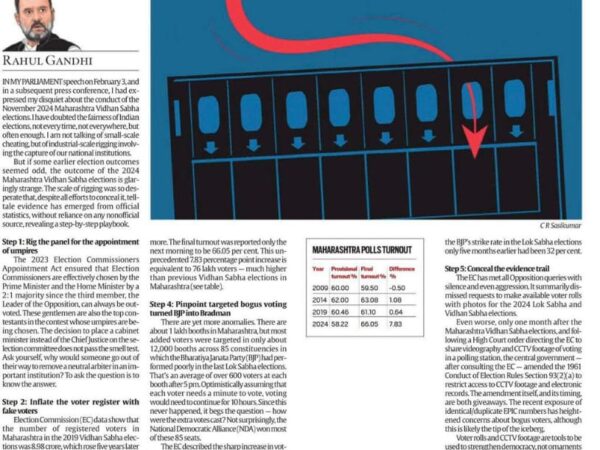

Time and again, the evidence walks into the room wearing a T-shirt and holding a cap table. Rahul Yadav, fresh off Housing.com and 4B Networks, raises money like the past never happened. Sandeep Aggarwal, convicted of insider trading, is treated like just another comeback story. Karan Bajaj helps inflate the edtech bubble and walks off to raise millions for cancer care with zero public accountability. The Jaggi brothers of Gensol spend public loans on luxury indulgences. And Byju Raveendran, whose name is now synonymous with financial wizardry of the wrong sort, remains an enduring legend of how far you can ride the hype before the spreadsheet explodes.

These men did not operate in shadows. Their arrogance was public. Their red flags were visible. Yet time and again, the capital came.

Why?

Because Indian VCs, much like the bureaucrats they pretend to disdain, have perfected the art of plausible deniability. They claim shock only in hindsight, if at all. They mourn only after the obituary has gone to print. In the meantime, they flood LinkedIn with platitudes about governance and grit and perseverance, and then, in practice, fund the founder who promises speed and scale at the cost of everything, not the one who shows spine or demonstrates principle of any kind other than that which pleases Mammon.

Ask them why they fund ethically suspect ventures, and you will get a PowerPoint’s worth of jargon: better boards, tighter governance, independent directors, frameworks. As if the presence of a checklist guarantees the absence of a con.

This is where the circularity of their argument becomes laughable, if it were not so tragic.

To say that ethical lapses can be solved by better governance is like saying:

- The way to stop theft is to make stealing illegal.

- The solution to corruption is to ensure everyone is honest.

- The cure for dishonesty is to ask people to please not lie.

- Or my personal favourite, prevent drowning by handing out swimwear.

It is a plea for virtue dressed up as process. It assumes the very thing it seeks to create. It confuses architecture with ethics, and compliance with conscience.

Governance, at its best, is a structure. But integrity is culture, and culture is enforced not by policy documents, but by consequences.

I had the pleasure of debating this recently with a well-decorated gentleman who insisted that integrity could be engineered post-investment, so long as there was a good board in place. We met in person. Cordially, if not constructively.

But here is the counterargument I never had the chance to finish.

Governance without the courage to walk away from a lucrative deal is not strategy. It is stagecraft. And even walking away is not enough.

Because many investors have walked away from startups that eventually imploded, but not because of ethical concerns. They walked because the numbers did not add up. Because the model did not scale. Because the CAC looked suspicious. Not the character.

They walked away for the safe reasons, not the right ones. For profits, not morals.

That is not integrity. That is actuarial caution.

Integrity is saying no even when the numbers work, because the founder does not. It is refusing to chase valuation when the fuel is fraud. It is not about risk management. It is about moral clarity. And it is vanishingly rare.

We do not need more decks and dashboards. We need people with backbones. People who will ask not just, “Will this make money?” but, “Should it?” People who understand that the founder’s relationship with truth matters more than their grasp of metrics. People who will say no to a deal not because the IRR is low, but because the ethics are lower.

And yes, we need diversity too, but not as token representation or thematic focus areas. We need it in who we trust, who we back, who we co-create with. Because integrity and inclusion are not separate domains. They are deeply intertwined. A system that cannot see the moral risk in its own reflections cannot possibly see the brilliance hidden in places it never looks.

I say this not as a righteous outsider, but as a recovering insider.

There was a time I had offices across continents, hundreds of staff, massive trade volumes, and the kind of access that lets you think you are indispensable. And I suspect I was insufferable. Power, especially financial power, has a way of convincing you that your opinion is insight, your prejudice is wisdom, and your tone is authority.

It has taken the slow unwinding of that life, the humility of collapse, and the quiet grace of rebuilding to understand how deaf power can be. And how much clarity comes when you no longer have anything to prove, or protect.

So when someone tries to win an argument by asking whether I have “even invested one rupee,” I am not offended. I am simply reminded. I have met that man before. In the mirror. A long time ago.

This is not about one man. It never was.

This is about a culture. A system. A story we keep telling ourselves.

That governance can replace integrity.

That funding equals wisdom.

That dissent is hostility.

That scale justifies silence.

We must stop telling this story.

Because if we do not, we will continue to invest in the same sins, again and again, only dressed in cleaner fonts, backed by sharper pitch decks, and presented with even greater conviction.

And one day, we will wake up and realise we built a generation of companies with no soul. If that day has not already come. Which I suspect it has.