Old Roots. New Rot.

It’s oddly fitting that India’s national tree is the banyan.

Majestic. Sprawling. Symbolic.

And, in many ecological contexts, invasive.

The Ficus benghalensis doesn’t grow like a tree. It spreads like a strategy. It drops aerial roots, colonises space, and suffocates whatever lies beneath. It survives not by coexisting, but by consuming. It suppresses surrounding growth and then stands tall, untouched, unchallenged, and very much alone.

Which makes it the perfect emblem for how India has historically treated knowledge, power, and commerce.

For thousands of years, the flow of knowledge wasn’t just limited. It was guarded.

Who could learn. What they could learn. In which language. From whom. At what stage of life.

All of it was dictated by birth, not merit.

We didn’t just prevent progress.

We criminalised collaboration.

And true competition.

Indeed, the thumb that Eklavya had to sacrifice? I don’t think he was the only one. There were a million Eklavyas. And a million severed thumbs.

No diversity of perspective. No cross-pollination of ideas.

No shared innovation between the mind that builds and the hand that makes.

What we got instead were silos.

Expertise that was hereditary, not shared.

Trade secrets that were caste secrets.

And wealth that was hoarded like ritual.

The Mughals didn’t invent this. Nor did the British.

They simply arrived and made the most of a system that already prioritised hierarchy over harmony.

They irrigated the rot.

Scaled it.

Systematised it.

But the first seeds? We planted those ourselves.

Why This Post Exists.

Today, I published (on LinkedIn) part two of a three-part essay on what I called the “operating system” of Indian business. I argued that cheating has become culture, not anomaly. Performance, not profit. Optics, not outcomes.

In it, I traced the rise of systemic rot through three eras: Mughal, British, and Licence Raj. A sweep, yes. But not a shallow one.

But someone I deeply respect wrote back with something that’s stayed with me since. He said:

Kedar, I follow your posts daily and they’re generally very sound, but I have a sense of disquiet about this one. It seems to suggest everything was clean and clear before the Mughals. Is that the idea you wish to convey?

Let me begin by saying this. I love questions like this. Not because they flatter my writing, but because they interrogate my assumptions. Especially when they come from friends who care more about the truth than the tone.

So, here’s my attempt to clarify.

Not to correct, but to expand.

Not to defend, but to deepen.

No, It Was Never Eden.

Let me be clear. I’m not suggesting that pre-Mughal India was a moral utopia of honest businessmen in khadi kurtas measuring purity by the tola.

We had casteism.

We had karma.

We had corruption.

The Hindu social order institutionalised a moral hierarchy where economic roles were not based on skill, but birth.

The merchant (Vaishya) was entitled to profit, but not prestige.

The labourer (Shudra) served, but did not own.

The Dalit existed outside the system altogether, denied dignity, access, and capital.

Caste didn’t just decide who could trade.

It decided who could touch the goods, who could profit from them, and who could speak about it in public.

Karma gave inequality a divine logic.

Dharma gave it a social instruction manual.

Justice and fairness were never part of the equation.

Even economically, India wasn’t some frictionless trading zone.

Feudalism. Temple monopolies. Land grants to Brahmins.

Artisanal castes without mobility.

Education, trade, knowledge, all gatekept. Reserved. For a few.

All of these testify to a deeply unequal, economically inefficient system that predated the Mughals by centuries.

So yes, the orchard was always vulnerable to rot.

What changed with the Mughals, and then the British, was the scale, the structure, and the statecraft of that rot.

The Mughal Upgrade.

Under Akbar, the Mughal empire introduced governance and revenue systems of unprecedented rigour:

- Detailed land surveys (Todar Mal’s revenue reforms)

- The zabt system, where tax was pre-fixed based on productivity, encouraging under-declaration

- The mansabdari system, where officers got land rights in exchange for loyalty, often at the cost of actual farmers

What this meant was that business, whether agrarian or mercantile, had to engage with a sprawling, extractive administrative machine.

Middlemen, tax collectors, clerks, and courtiers all took their cut.

The system wasn’t occasionally corrupt. It was designed to be corruptible.

And the businessman, far from being a passive victim, adapted.

He learnt the dance. Bribes, barter, books fudged in Persian.

He learnt to “put one over.”

Not as rebellion.

But as survival strategy.

It was no longer cheating.

It was working the system.

And crucially, access to that system, permission to profit, was still confined to the twice-born.

Criminality may have expanded.

Opportunity did not.

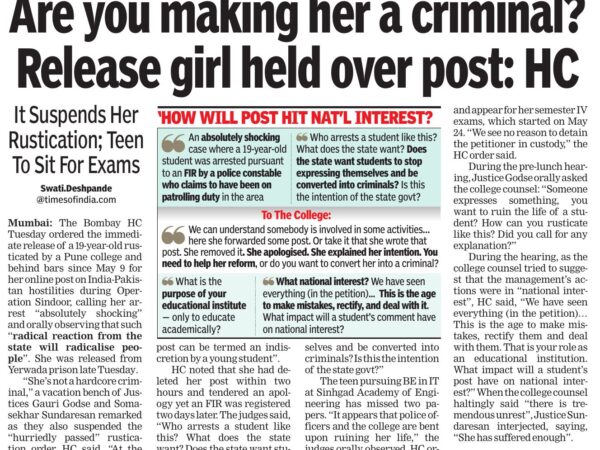

The British Formalisation.

The British, ever the bureaucratic colonisers, didn’t invent corruption.

They gave it a filing cabinet and a legal code.

- Permanent Settlement made zamindars into revenue-maximising landlords, institutionalising tenant exploitation

- Weavers in Murshidabad and Dhaka weren’t outcompeted. They were crippled by design

- Artisan castes, already marginalised, were now economically extinguished

We didn’t just lose our industries.

We were penalised for having them.

The Indian businessman didn’t just learn to cut corners.

He built entire identities around cutting corners.

This wasn’t theft.

It was adaptation.

It was muscle memory.

The con became cultural.

The hustle became heritage.

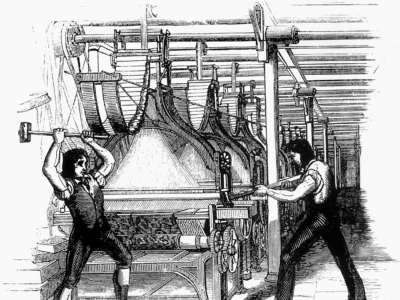

Brown Sahib. Same Game.

By the time independence arrived, the colonial machinery wasn’t dismantled.

It was repainted.

The bureaucracy stayed opaque.

The process became sacred.

Rules were meant to be broken.

And everyone knew someone who knew someone.

The trader, by now, was a hybrid:

- Mughal-inherited mistrust of the state

- British-inherited love of loopholes

- Caste-inherited impunity, where privilege shielded risk and ethics were optional within one’s biradari

Karma still justified inequality.

Dharma still enforced roles.

But now, there was capital.

And capital didn’t trickle down.

It gated itself behind surnames and social clubs.

Add to that a homegrown hustle culture, fuelled by jugaad, contacts, and compliance cosplay.

This isn’t a new infection.

It’s an old instinct.

A well-trained reflex.

But not everyone had the luxury to train that muscle.

Those denied land, literacy, and legacy didn’t get to hustle.

They didn’t skim.

They got skimmed.

Before the Mughals? Still Messy.

So, was pre-Mughal India clean?

No. Once again, no.

But it was fragmented.

In scale. In reach. In ideology.

The pan-Indian normalisation of gaming the system began with the Mughals, was industrialised by the British, and became tradition during the Licence Raj.

If you must imagine an orchard, don’t imagine Eden.

Imagine isolated groves, some rotting quietly.

Then came irrigation.

Then the pesticide.

Then we built a greenhouse.

But remember, only a few castes were allowed to farm.

The rest were told to pluck fruit, pay rent, and never touch the ledger.

In Defence of the Gardeners.

Let me pause here to defend the gardeners.

This is not a takedown of Nehru, Patel, Ambedkar, or our founding generation.

They inherited a traumatised population.

A looted economy.

An empty treasury.

A hostile neighbour.

A fractured identity.

And a business class fluent in evasion, not innovation.

So, they did what was necessary.

They centralised. Subsidised. Stabilised.

They built institutions before markets.

They chose access over ambition.

Equity over efficiency.

Nation-building over profit-maximising.

If you are reading this on a smartphone, typing in English, and were raised on subsidised food, fuel, or education, please know.

You are a product of Indian socialism.

It wasn’t perfect.

Yes, it slowed us down.

But it also kept us alive long enough to have this debate.

The problem isn’t that India was too socialist.

The problem is that Indian business learnt to game socialism instead of outgrowing it.

And that, my friends, is not on Nehru.

It’s on us.

Tracing the Rot.

To my friend, and to everyone who found the original post unsettling, thank you.

This is the kind of disquiet I value.

Every polemic needs a pause.

Every generalisation needs a genealogy.

No, history is never clean.

But it does have patterns.

And if we want to clear this orchard,

We must first understand what took root.

How it spread.

And why we keep mistaking rot for tradition.

Even when the national tree is the banyan.