Every April, as if on cue, a peculiar restlessness begins to simmer in the salons and WhatsApp groups of India’s polite society. It’s Dalit History Month, and with it come the towering, inconvenient anniversaries of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, Mahatma Phule, and Dr B.R. Ambedkar, men whose very names cause a curious tightening of the jaw among those who prefer their history with the edges sanded off. And right on schedule, as sure as mangoes in May, emerge the murmurs, casual, smug, dressed in the language of “informed critique”

The Indian Constitution? Oh please. Just a copy-paste job from the Americans, the French, the Irish. Nothing original. A plagiarised document.

Let’s humour them, briefly. Let’s pretend it comes from curiosity rather than caste. From genuine inquiry rather than the persistent ache of having to share power. Let’s answer it as if it were sincere.

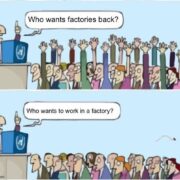

If you were tasked with drafting a Constitution for a country of 350 million, newly liberated, bleeding from the Partition, straining under centuries of colonial extraction and an even older scaffolding of caste, would you begin from first principles? Would you reinvent democracy like it’s the number zero? Or would you do what any serious nation-builder, any competent engineer, any pragmatic architect would do: study what already exists, understand what has worked, adapt what fits, discard what doesn’t, and build with clarity and purpose?

Babasaheb Ambedkar wasn’t just qualified to do this. He was terrifyingly overqualified. A man whose academic record reads like a challenge to mediocrity itself: doctorates in economics, degrees in law and political science, scholar of Sanskrit and Persian and Pali, one of the most deeply read minds of his generation, not just in India, but across the world. He didn’t stumble into The Drafting Committee. He was the only person who could have done what needed doing. Nehru knew it. And appointed him even when he was not a Congressman.

And yes, he borrowed. Of course he did. Everyone borrows. Every civilisation is a second draft of something older. The French Revolution drew from Enlightenment thinkers who drew from ancient Greece and Rome. The American Constitution borrowed heavily from British common law, the Magna Carta, Montesquieu, Locke, and even the governance systems of the Iroquois Confederacy. The Irish Constitution was steeped in Catholic social teaching, British legal structure, and its own anti-colonial struggle. Babasaheb didn’t plagiarise, he curated. He translated universal ideals into Indian realities. He didn’t just lift sentences, he interrogated them, filtered them through a caste-ravaged society, tempered them with our context, and hammered them into a framework that could hold this impossibly diverse nation together.

Because everyone copies. That isn’t the scandal. The only question worth asking is: what did you choose to copy? From whom? And to what end?

So let’s talk about who else was copying, while Babasaheb was building.

Let’s talk about the ideological ancestors of those who call him a fraud today.

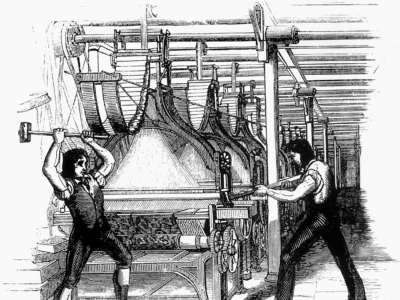

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, founded in 1925, two decades before the Constitution, wasn’t looking to France or America or Ireland for inspiration. They were looking to Rome. Fascist Rome. Their uniforms, their salutes, their obsession with order and hierarchy, their disdain for dissent, all lovingly imported from Mussolini’s Italy. Their early literature held up Nazi Germany as a model of national unity and cultural strength. Their leaders didn’t quote Thomas Paine or John Stuart Mill. They quoted Hitler. If we are going to interrogate the roots of borrowed ideologies, let us do so honestly and follow those roots all the way down.

Babasaheb copied liberty. The Sangh copied subjugation. Babasaheb built for inclusion. They built for exclusion. He wanted freedom and equality. They wanted obedience and inequity. He reached for ideas that would uplift the most oppressed. They reached for ideologies that justified oppression as destiny.

And yet, they question his legitimacy!

And here’s where the farce becomes fury.

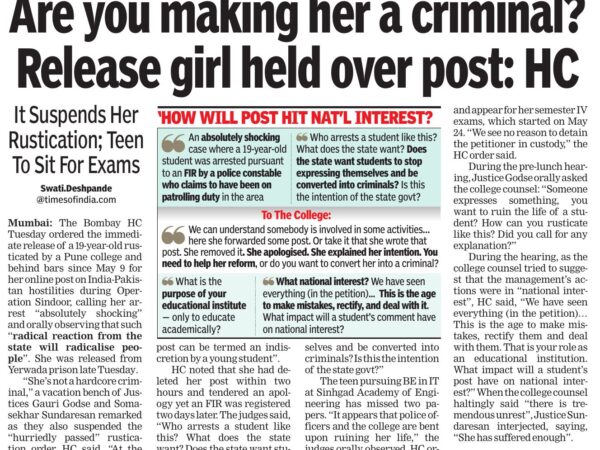

If your real issue were with the Constitution, it offers you a civilised, structured way to change it. The right to amend it was built into the very document you despise, because Babasaheb wasn’t arrogant. He knew that nations evolve, and that laws must, too. If you truly believed this document was broken, you’d follow due process and fix it. But you don’t want to fix it. You want to delegitimise it. Because what you really cannot stomach is not the content of the Constitution, it’s the authorship. You cannot bear that a man you were taught to think of as less than you, as unworthy, as impure, as uninvited, had the intellect, the discipline, and the moral authority to do what you never could.

And we see this pattern everywhere.

When someone uses AI to write clearly, you don’t complain because they used a tool, you complain that someone you thought beneath you, because English wasn’t their first language, now writes better than you. When Rahul Gandhi walks with truck drivers, you scoff, not because he walked, but because someone might actually be watching, and worse, relating, as opposed to the Emperor who only dines with celebrities, billionaires, and heads of states. When marginalised communities speak fluently, powerfully, with confidence, you call it mimicry, or PR, or worse, theft.

It is never about what you say it is.

It was never about grammar. It was about the fact that the dispossessed now speak with precision.

It was never about originality. It was about the fact that a Dalit man stitched together the soul of a new republic while you were still clinging to the corpse of a crumbling hierarchy.

It was never about methods. It was always about power.

And now that the rules are being rewritten, now that the margins have found microphones, now that those you silenced for generations are not only speaking but being heard, you are panicking.

Because history, finally, is no longer being written for them.

It is being written by them.

And it is looking you in the eye.

Saying, without rage, without apology, without asking, it’s our turn now.