“Never interrupt your enemy when he is making a mistake.” ~Napoleon Bonaparte

There’s an old, possibly apocryphal quote attributed to a Mumbai police commissioner during the height of the city’s mafia wars: “As long as they keep killing each other, I don’t see a problem.” It’s a bit grim, a touch callous perhaps, but there is something to be said for the quiet efficiency of that position when watching entrenched power groups begin to turn on one another. It is, in many ways, the only viable posture when faced with factions that have long operated above scrutiny and outside accountability, now suddenly confronted with the consequences of their own contradictions.

Take, for example, Baba Ramdev’s latest public gambit. In a video that is neither new in tone nor surprising in content, he suggested that a certain red syrup, clearly Rooh Afza, was indirectly funding conversions and madrasa education. The implication, unspoken but unmistakable, was that buying this syrup was not simply a beverage choice but a subversive act against the Hindu nation. It is the sort of rhetoric that has become second nature: vague enough for plausible deniability, pointed enough to activate a certain audience.

But this episode, unlike his usual provocations, seemed to have more than just market competition behind it. Hamdard Laboratories, the company behind Rooh Afza, is structured as a waqf trust, a status that comes with religious overtones, charitable obligations, and, crucially, significant real estate holdings across India. In light of the recent amendments and murmurs around the Waqf Act, it is not entirely inconceivable that this was less about syrup and more about softening public sentiment in preparation for a larger land-and-control play. If so, it is a long game, albeit one launched with characteristically clumsy, though predictable, theatrics. Or maybe the truth is simpler: Hamdard paid Ramdev to create a buzz around its so-comatose-it’s-dead brand. Occam’s Razor and all. Who knows the truth?

What we do know is that what followed was almost formulaic in its absurdity. In response to the call for boycott, a significant segment of the online population declared their allegiance to Rooh Afza with great theatricality. Bottles were purchased, photos were posted, and what was once a mildly nostalgic summer drink became, overnight, a totem of resistance. The entire episode was equal parts theatre and farce: two syrup merchants, one draped in saffron traditional appeal and the other in green inherited goodwill, competing not for market share but for moral high ground.

For those of us who still believe that not everything must be consumed, interpreted, or resisted along communal lines, there is little incentive to participate. I grew up with Rooh Afza, as many did, and while it holds a certain sensory place in memory, it is, let’s be honest, just sugar in a bottle. As is its rival. When two peddlers of literal coloured sugar syrup engage in a moral skirmish, neutrality isn’t cowardice. It’s discernment.

But wait. I am not done with my argument on why Napoleon’s maxim is my guiding star for this sort of stuff.

Shift now to Pune, where the Deenanath Mangeshkar Hospital, named for the patriarch of one of India’s most revered musical dynasties, has become the unlikely epicentre of a different conflict. A woman has died. Her family alleges negligence. She was the wife of a BJP office-bearer. The hospital, run by a trust with close ties to the Mangeshkar family, has long been whispered about in Pune as an institution whose outward image of charity conceals a very private, very cutthroat operational model. Its treatment of patients, particularly poor ones, though the cashier does not distinguish between them and the moneybags when it comes to billing, has often raised questions. But what makes this case particularly combustible to me is not the tragedy (and it is one, involving an innocent’s death), but the caste dynamics it has reignited.

The Mangeshkars, by birth and by affiliation, belong to the Gaud Saraswat Brahmin community, a class whose historical influence far outweighs its demographic weight. It is not unique to India; every society has had its priestly class, adept not at ruling directly, but at staying proximate to the seat of power, whispering doctrine, and shaping discourse. In Maharashtra, this class built the very ideological infrastructure of the modern Hindu right. From Savarkar to Moonje, from Hedgewar to Golwalkar, from Godse to Apte, it was a coterie of Marathi Brahmins that drafted the language, worldview, and anxieties of Hindutva, not to mention the strategy and tactics for action.

And yet today, a rift is visible. The Brahmins of Pune, long the intellectual, institutional, and economic ballast of the BJP in Maharashtra, find themselves uneasy. The party, with its electoral eye on Marathas and OBCs, has not leapt to the hospital’s defence with the reflexive loyalty expected of it. In fact, silence, the most telling betrayal, seems to be the chosen strategy.

And this silence is doubly ironic when one considers that the man at the helm of the state is Devendra Fadnavis, a Brahmin himself, yes, but also a political heir, at least symbolically, to the original Fadnavis of the Maratha confederacy, a bureaucratic master tactician who once balanced, manipulated, and co-opted the Maratha sardars to maintain his grip on power. A man Machiavelli could have learnt from. Today’s Fadnavis appears not unlike his namesake, playing a careful, transactional game between restive allies and shifting social arithmetic in an attempt to divide and rule.

The conflict may fizzle. It may flare. But it reveals something instructive: when power is negotiated through identity, its continuity is always under negotiation. Regardless of who wins, whether the BJP manages to smother the Puneri Brahmins and put them back in line, showing them their place in the new hierarchy of power, or whether the Brahmins reassert their supremacy over their own creation, whichever way this story goes, both parties will emerge weaker. And frankly, I won’t be unhappy with either of the two outcomes. Or both of them.

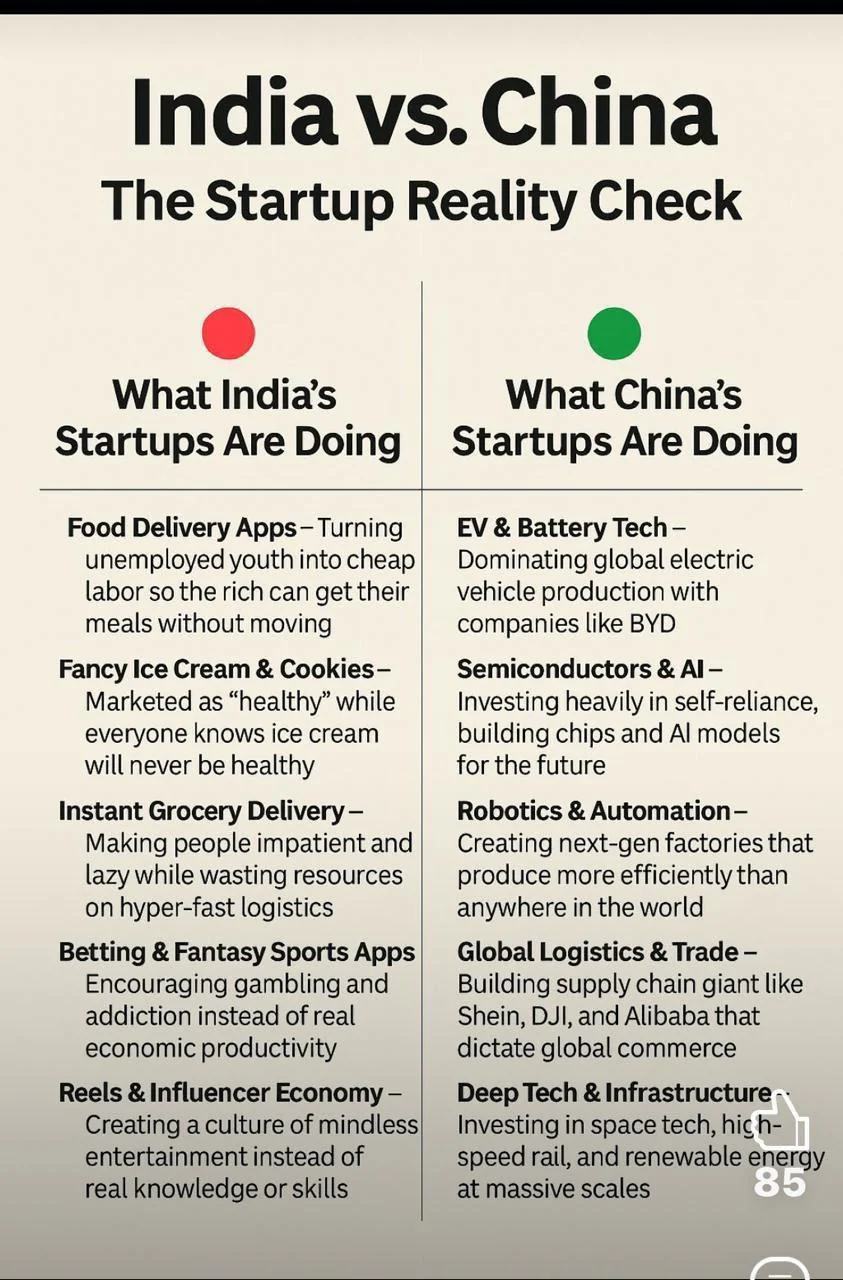

The third front in this slow unravelling is not spiritual or caste-based, but economic and digital. India’s startup ecosystem, long heralded as the face of aspirational India, is now locked in a public quarrel with the very state apparatus it once flattered. At the Startup Mahakumbh, an event with a name as clunky as it is cringeworthy, Commerce Minister Piyush Goyal delivered an entire speech chastising Indian entrepreneurs for being too focused on convenience, too reliant on exploiting cheap labour, and too distracted by delivery apps to build anything of long-term technological value. This wasn’t an offhand comment. It was a thesis. But a thesis that was born of a meme being uploaded into ChatGPT and asked to be expanded into a full-length speech, with a prompt that it must talk over the audience and berate, punch down and mock, and absolve the government of any part it may have played in the state of entrepreneurship in India by shifting the blame, while at the same time, creating meme-worthy punchlines along the way in a smug, self-satisfied way.

And, as expected by everyone but the honourable minister himself, it landed poorly. Particularly among the techbros, the tech ‘evangelists’ who believe an app can solve child hunger, caste injustice, and potholes, provided the UI is sleek enough. These are the chaps who once thought they could code their way to ‘Viksit Bharat’, who mouthed the right slogans and tagged the right ministers, who built VC-money-backed apps to disrupt chai, chapattis, and common sense in the mornings, and made podcasts talking about their hustle by evening. In the weeks since, a stream of angrily worded open letters, public rebuttals, and LinkedIn laments have emerged, pointing out, often with restrained (and sometimes passive-aggressive) politeness, that bureaucratic apathy, regulatory chaos, and red-tape lethargy are not exactly the soil in which innovation thrives.

These founders are not traditional dissenters. Quite the opposite, in fact. They are the original cheerleaders, the ones who posed with policy-makers, echoed slogans, and painted PowerPoint slides with tricolour optimism, even going so far as public flattery on live TV. But now, the transactional relationship is fraying. The state appears less a partner than a disinterested landlord, happy to collect credit when it suits and rent when it’s due, but slow to fix the plumbing.

So when the Puneri Brahmins and the BJP confront each other across a hospital ward in a war of attrition, when Lala Ramdev tries to bait another red-coloured sugar syrup maker into a proxy war and fails, when the privileged and entitled techbros and the regime they tried to please by bending over backwards fall out in a whirl of bureaucratic indifference and wounded pride, what, exactly, should the rest of us do?

The answer is as old as it is simple. I call it Napoleon’s Razor.

Do not intervene. Do not align. Do not mistake spectacle for cause.

And above all, don’t drink the syrup. Instead, let them drown in their own concoction.