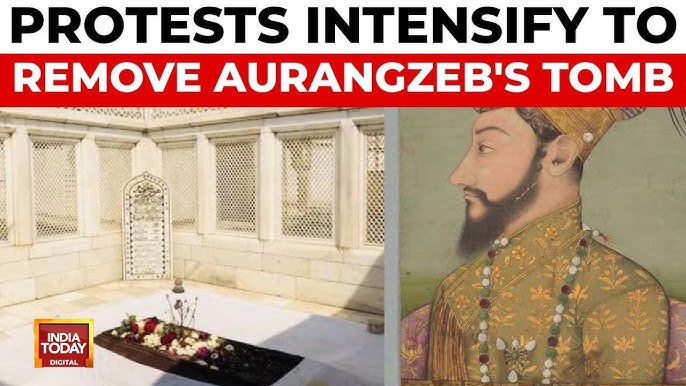

In Khuldabad, Maharashtra, lies the unassuming grave of a long-dead emperor. Aurangzeb Alamgir, once the ruler of a vast and fractious empire, requested to be buried in a simple grave, the cost covered by the sale of caps he stitched with his own hands. In life, he was a puritanical autocrat, a man who imposed religious orthodoxy with violence, who persecuted communities, razed temples, and ruled with an iron grip. A tyrant by any measure, and one of the most joyless bigots to sit on the Peacock Throne.

Yet even he, as per the standards of Indian tradition, was buried with dignity.

Over 318 years later, his legacy remains rightly contested and debated. But now, the demand is not for scholarly reassessment or even spirited condemnation. It is for the desecration of his grave. This macabre desire, cloaked in the language of cultural reclamation, is perhaps the most un-Indian act possible, especially from those who claim to act in the name of Indian culture.

For centuries, India has treated the dead, friend or foe, saint or tyrant, with reverence.

Ashoka, after a brutal war that filled the Kalinga plains with corpses, did not order the desecration of enemy dead. He embraced Dhamma and ensured respect for all life, even in memory.

When Chh. Shivaji killed the Bijapuri general Afzal Khan in self-defence during their infamous meeting at Pratapgad, he ensured that his fallen enemy was accorded full Islamic funeral rites. Afzal Khan’s head was presented first to Jijabai and then to the Goddess Bhavani as a symbolic gesture of gratitude. But his body was buried with dignity, and a tomb still stands in his memory. A formidable adversary, laid to rest with honour by the very man he came to kill. That is Indian tradition. That is the Maratha legacy. Maharashtra Dharma.

This is not just something that happened long ago, though. Indian civilisation’s instinct to draw a line at the grave or the funeral pyre has endured through the centuries, right up to modern times.

Nathuram Godse, the assassin of the Mahatma, was given a trial under due process. Upon execution, he was cremated according to Hindu rites. His ashes are being preserved for decades by admirers, waiting to be immersed in the Indus. The man murdered the father of the nation, yet the nation did not stoop to desecration.

Ajmal Kasab, a Pakistani terrorist who mowed down innocents in the 2008 Mumbai attacks, was hanged after a full and fair trial. No triumphant spectacle was made of his death. His body was buried in an undisclosed location, handled with the dignity that India’s laws and customs quietly extend, even to monsters.

Satwant Singh and Kehar Singh, convicted for their roles in the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, were executed after due legal process. Their last rites were conducted with religious dignity. They had conspired in the killing of a head of government. Yet even then, the state honoured its duty to the dead.

This is not weakness. It is strength.

It is the maturity of a people who understand that civilisations are not judged by how they treat saints, but by how they handle sinners. And in India, we do not raise mobs against graves. We do not exhume the past to fight the present. Our culture has always understood that the dignity of the dead is a reflection of the dignity of the living.

In modern times, the Indian Army, no stranger to violent conflict, has codified respect for the dead in its doctrine, its Human Rights Charter, and its conduct in war. In the 1999 Kargil War, for example, the Indian Army recovered the bodies of Pakistani soldiers, invaders by every account, and returned them with military honours. Not because it was popular, but because it was right. Geneva Convention I, Article 16, obliges combatants to search for and honour the dead, but the Indian Army did not need a foreign law to know what was decent.

Even in counter-insurgency operations, where identification is murky and tempers run high, the Army’s standard operating procedures insist on respectful handling of the dead. Enemies are buried according to their faith. Civilians are never stripped of dignity, even posthumously. This is not to say that bad actors do not act in contravention to the convention, law, and decency. The point is that respect towards the dead is enshrined in military law, and any breach is an anomaly and not the norm.

This respect extends beyond formal military settings. In Indian villages, when a body is found, strangers gather to perform last rites. It is not law that compels them, but an old cultural reflex. A millennia-old conscience that whispers: “Let the dead rest.” This was seen very recently during the COVID pandemic when good Samaritans who helped perform the last rites of people they did not know came forward as effortlessly as they receded into the background when the virus subsided. No fanfare. No moralistic grandstanding. Just doing their “dharma”.

The very phrase Hindus say upon death, “Om Shanti”, is not merely a poetic equivalent of “Rest in Peace.” It is a deeply spiritual invocation, a hope for peace, yes, but more importantly for liberation, for moksha. The soul is not wished rest alone, but freedom from the burdens of karma and from the cycle of rebirth. Even the wicked are released to the cosmic order, not dragged back, exhumed, and flogged by the living centuries later.

And here, history offers its quiet but thunderous rebuttal to today’s angry calls. If any people had the cause, the opportunity, and the power to desecrate Aurangzeb’s grave, it was the Marathas. Their struggle against him was bitter and generational. Yet when Aurangzeb died in 1707 and the Maratha Empire rose to dominance soon after, no effort was made to defile his tomb. For over 111 years, through the rise and rule of the Peshwas and the expansion of Maratha power until their final defeat in 1818, Aurangzeb’s grave remained untouched. Successive generations of Maratha rulers, proud warriors with the means and memory of his cruelty, let him lie in peace.

If they, so close in blood and loss, could leave him buried, who are we, three centuries removed, to unearth his corpse in outrage?

And so we return to Aurangzeb’s grave.

Desecrating the grave of a long-dead emperor is not an act of justice. It is an act of fear. Fear that the present cannot be wrestled without first exhuming the past. But corpses do not govern. The living do. A society that prides itself on samskaras, on shraddha, on karma and the cycle of rebirth cannot also demand vengeance on a skeleton.

The real desecration is in the psyche. To adapt a Zen Buddhist parable: a young monk is shocked when an elder monk carries a beautiful woman across a river. “But we are not to touch women,” he exclaims later. The elder replies, “I left her at the riverbank. Why are you still carrying her?”

Aurangzeb was buried in 1707. The man is long gone.

The question is, why are we still carrying him?