It begins, as most spectacularly daft ideas do, with a metaphor.

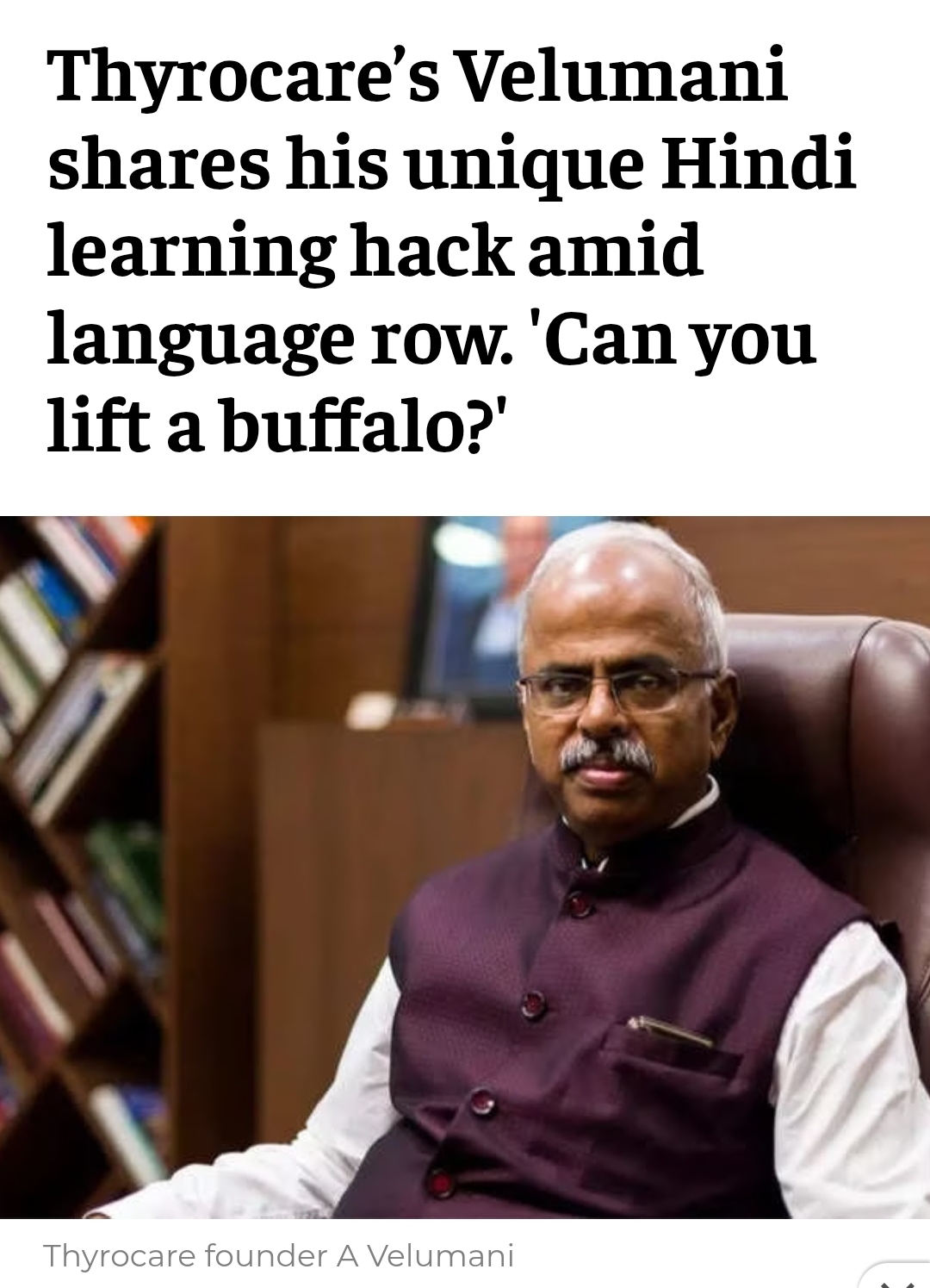

“Can you lift a newborn buffalo?” asked Dr A. Velumani, entrepreneur, diagnostician, philosopher of improbable strength, and, on this occasion, motivational cattle enthusiast. Flanked in spirit by Subra and Muthy, the Athos and Porthos to Velu’s Aramis, he posed the question with the gravity of a man who has clearly not been introduced to Newton’s laws or a full-grown Murrah (or more probably, a Toda).

“Yes,” said the obliging student, presumably unaware of what was about to happen to his spinal cord.

“Well then,” beamed Velumani. “If you do this every day, you shall one day lift a fully grown buffalo.”

A charming tale. A triumph of motivation over musculoskeletal reality.

And now, inevitably, this logic, the buffalo-hoisting principle, is being applied to language policy. Specifically, to learning Hindi.

We are told that Hindi is not difficult. You simply begin. Then continue. And continue again. Like lifting buffaloes. Or buildings. Or the national mood.

Can you lift a brick? Marvellous. Tomorrow, try two. By year-end, you’re squatting a semi-detached. Or flying. Begin by leaping six inches. Add two more daily. By summer, you’re clearing the Qutub Minar in a single bound, with a victory cry in Devanagari script.

The trouble with such analogies, aside from being anatomically implausible and mildly threatening, is that they flatten complex cultural realities into inspirational fridge magnets.

Velumani’s buffalo, much like this country’s language policy, is not so much unliftable as it is uninvited. It is not the difficulty of the task that’s troubling. It is the sudden appearance of a large, insistent bovine specimen in one’s drawing room, and the chirpy command that one must now lift it. Daily. Diligently. Without complaint.

No buffaloes, or indeed, Velus, were harmed during the AI generation of this image.

The problem, you see, is not with Hindi. Hindi is perfectly fine. Sturdy, melodious, a language capable of romance, revolution, and reality television. Nobody is raising objections to its existence. The objection is to its compulsory enthusiasm. The problem isn’t the “bhains”. It is the “lathi”.

Tamilians are not saying they cannot learn Hindi. They are saying they were never asked whether they wished to. A rather crucial detail, especially in a democracy.

And it is not only Tamil. Speakers of Awadhi, Braj, Bhojpuri, Magahi, Maithili, Rajasthani, Chhattisgarhi, languages with glorious histories and more literary pedigree than Delhi has signage, have watched as theirs were quietly reclassified as “dialects of Hindi”.

Not by linguistic consensus, but by bureaucratic fiat, and not a small bit of subterfuge. With the gentle finality of a government stamp and the chilling efficiency of a form marked “Other”.

The erosion is not loud. It is not even obvious. It is slow. Precise. Clinical. Over time, all the letters begin to look the same. The words blur. The meanings slip. What were once songs, stories, idioms and identities become black marks on a page. Indecipherable.

Some might even say: The shape of a buffalo.

And then one day, as you gaze across the linguistic savannah and find your own mother tongue classified under “Misc.”, you find yourself muttering the national epitaph of exasperation:

Gayi bhains paani mein.

The buffalo’s gone into the water. Along with it, perhaps, a little of your language, your autonomy, and your ability to say “no, thank you” in your own words.

And what a pity that is, in a country where no two cups of tea taste the same, where the spices change by district and the nose-ring by postal code. A nation of contradictions, yes, but also one of extraordinary compatibility. A glorious, ongoing argument that somehow holds.

To insist on one language, particularly when gift-wrapped in the insufferably well-meaning tyranny of “What’s the harm in learning it?”, is to miss the point entirely.

India is not supposed to match. It is not a form to be filled out in triplicate. It is a jam session. A mosaic. A permanently unfinished symphony in twenty-eight keys and three time signatures. A jazz band with a dozen maestros, none of them with the same instrument, but all of them coming together to play kickass music you cannot hear anywhere else!

Its soul lies in dissonance. Its rhythm in improvisation.

And so we return, inevitably, to the buffalo.

Lumbering. Earnest. And wholly misplaced.

Because buffaloes, like languages, like nations, and certainly like state-mandated unity drives, are not for lifting.

Especially not when they have barged into your living room, knocked over the bookshelf, stood on the carpet, eaten the ficus, and are now blinking at you expectantly, while someone in a Nehru jacket (oh, wait, it is called a Modi jacket now, with nary a nod to the irony of appropriation, methinks) insists you should be grateful for the opportunity. In Hindi.

Gayi bhains paani mein, indeed.