Yesterday, I asked whether morality is just a privilege of those with full stomachs. The responses poured in, some thoughtful, some outraged, and some performing such spectacular mental gymnastics that they deserved a spot at the next Olympics.

The key objections were:

- The Honest Poor: “But some starving people refuse to steal! Does that not prove morality exists independent of hunger?”

- The Outlier Argument: “Morality should be judged in normal circumstances, not in times of crisis.”

- The Appeal to Objectivity/Universality: “If we excuse morality during extreme situations, where do we draw the line?”

- The Thin End of the Wedge: “If we justify theft under desperate conditions, is that not a slippery slope into lawlessness?”

Each of these arguments, while seemingly solid, has some rather inconvenient cracks. Let us explore.

1. The Honest Poor.

The “Starving but honest farmer” sounds almost poetic, like “The noble savage,” something straight out of an Amar Chitra Katha comic, or the white colonialist’s handbook (no, not the Bible; I mean the figurative one, but I see your point). The poor farmer who watches their child starve but refuses to steal because of their unyielding moral fibre. A noble story, indeed. Except, like most noble stories, it conveniently ignores power structures, systemic oppression, and good old-fashioned fear.

This farmer is not moral in some grand philosophical sense. They are conditioned. Their refusal to steal is not a triumph of morality but a victory for centuries of religious indoctrination, social control, and economic exploitation. They are taught that their suffering is not a failure of an unfair system but a divine test, and if the farmer is in India, then it is spun as a karmic punishment, a fate to be stoicly lived through because of past sins, and/or the shame of being born in a particular caste.

The other indoctrination is that their impoverished state is their own personal inadequacy, and if only they had worked hard, or studied well, or taken more risks (whatever that means), they’d not be starving.

Their hunger is, in effect, their (or their ancestors’) fault.

They are convinced that in some way, they deserve their hunger.

And should they dare question it? Enter social and state violence.

- Spiritual retribution: “Stealing is a sin. God will punish you.”

- Social pressure: “The village will shun you. You will lose honour.”

- State violence: “The police will arrest you. The courts will crush you.”

So, is this morality? Or is it systematic coercion dressed up as virtue?

2. The Outlier Argument.

The “Morality should be measured in normal times” line of thought is the classic “Free speech only for things I like” argument, but applied to ethics. This is the idea that we should judge morality only in everyday, stable conditions because crises are exceptions, not the rule.

Here is the problem. Morality that only works in good times is not morality. It is etiquette.

- Everyone is polite at a dinner party. That does not make them good people.

- Everyone follows traffic rules in broad daylight. That does not mean they will stop at two in the morning when nobody is watching.

- Everyone is civil when there is food on the table. The real question is what happens when there is only one piece of bread left.

In fact, just a couple of days ago, I wrote of my father’s beliefs that, “A gentleman is one who does the right thing when no one is looking, especially when no one is looking.” Morality, much like character, is not tested when things are easy. It is tested when everything is on fire.

3. The Appeal to Objectivity/Universality.

Some say, “If we justify theft in extreme situations, does that mean all morality is flexible? Where do we draw the line? Who decides where to stop?”

Let us flip the question. If we do not recognise morality’s flexibility, are we prepared to say that starving people must suffer just to uphold a rigid principle?

Morality is not a universal, unbending truth. It is a tool, one we use to create functional societies. The goal is not to uphold rules for their own sake but to create a world where the need to break them is minimised.

If people must steal to survive, the problem is not the theft. The problem is the world we have built that leaves them with no other choice.

4. The Thin End of the Wedge.

If we justify morality’s flexibility, does that mean anyone can now excuse their wrongdoing with “I was desperate”? Will this not lead to lawlessness?

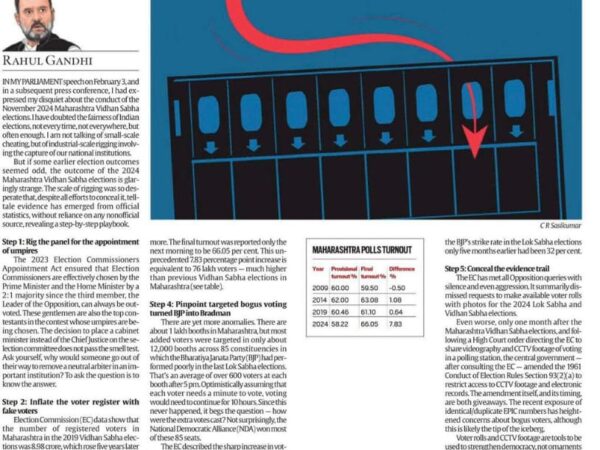

That is a fair concern, but let us look at who actually gets away with immorality today.

- A hungry person steals food. Arrested in hours. Jailed without trial for years before the case comes up.

- A billionaire launders ten thousand crore rupees. Flies to another country, holds press conferences from the beach surrounded by beautiful models, and tweets motivational quotes.

The truth is, immorality is already rampant. It is just conveniently ignored when committed by the powerful.

So, if the real fear is lawlessness, let us begin by holding those at the top accountable before we start lecturing the hungry about morality.

Or would that be going too far outside our comfortable zones from which we virtue signal about stealing & property, consent & hard work, and laws & justice?

But Here Is Why There Is Hope.

If all of this sounds bleak, it is because the world often is. The weight of history is heavy, and the systems that benefit from maintaining inequality are deeply entrenched.

And yet, change happens.

How? Because we question.

Every time someone asks, “Why is it this way?”, every time a community refuses to accept suffering as destiny, every time a movement rises to challenge injustice, that is progress. That is one step ahead in our collective evolution as a species that has somehow stumbled upon consciousness. And is not trying to use it.

We are not hopeless. We are not powerless. We have, in fact, spent centuries dismantling systems that once seemed immovable.

- Democracy, despite its obvious flaws, was built to flatten hierarchies and regulate excesses.

- Human rights movements have fought against entrenched oppression and systemic wrongs.

- Legal and social reforms have overturned injustices once considered normal, through much hard work, and I dare say, opposition from the very society the reformers were trying to better.

- Capitalism, for all its greed and excess, has been the most effective system in history for lifting people out of poverty, giving them dreams & aspirations, and encouraging them to pursue happiness.

Yes, you read that last one correctly. Capitalism.

This might come as a shock to those who assume that anyone talking about hungry children and inequality must also be preaching communism. But here is the truth. Democracy and capitalism, for all their flaws, are the only real tools we have to fix this mess.

- Capitalism might be ruthless, but it creates wealth, drives innovation, and funds the very welfare systems that attempt to redistribute resources. Without it, democracy collapses under the weight of economic stagnation and turns into a dictatorship of the few.

- Democracy, in turn, keeps capitalism in check and people in control by basing itself on the belief that capitalism must serve the people. “The Sabbath was made for man, and not man for the Sabbath.” Without democratic regulation, capitalism mutates into oligarchy, where a handful of corporations own everything, and the rest of us fight over scraps.

Look at countries where capitalism has overtaken democracy, where there is massive inequality, stagnant wages, and billionaires dodging taxes while workers live pay cheque-to-pay cheque. These are oligarchies.

On the other hand, look at places where democracy has overtaken capitalism, where state-controlled economies promise equality but deliver misery, corruption, and shortages. These are mobocracies.

The only societies that can close the gap of inequality without strangulating enterprise and innovation will be the ones where capitalism and democracy balance each other.

Indeed, Nordic countries like Finland, Denmark, and the Netherlands, with high economic freedom and strong democratic institutions, have done more to eradicate poverty and create happy societies than any ideological utopia like the USA and the erstwhile USSR ever could.

In fact, once you think about it, the real problem is not capitalism or democracy. It is when one overtakes the other, when the principles and ideological extremes of one or the both of them override the very real human needs for happiness and stability.

- Too much capitalism without adequate democracy, and you get corporate rule, wealth hoarding, and unchecked greed of a handful of oligarchs demanding to own everything.

- Too much democracy without true capitalism, and you get economic collapse, stagnation, and bureaucratic paralysis of a bulging administration, overweighed with controlling everything.

The key to progress is not in destroying these systems, but in making them work better together.

So, no, we are not doomed. As long as we keep questioning, balancing, and refining, we can keep moving forward.

Because morality should not be a luxury of the well-fed. It should be a foundation of a truly just world.

Final Note: A Brutally Honest Disclaimer.

Look, morality is complicated. Like, really complicated. If you think you have it all figured out, congratulations. You are either a saint or a sociopath. Most of us, mere mortals, stumble through life making it up as we go along, shifting our moral goalposts whenever it suits us, and pretending we have always had a consistent code.

So, before you run off to demand that others adhere to your personal brand of righteousness, maybe take a minute. Maybe, just maybe, ask yourself how often you conveniently tweak your own principles when they become inconvenient.

To put it bluntly: fix yourself first.

And if that sounds familiar, it is because I have shamelessly stolen it from those in-flight safety announcements.

“In case of emergency, calibrate your own moral compass before assisting others.”

Thank you for reading this far. It means you either care about morality or enjoy watching a slow-motion intellectual car crash. Either way, I appreciate you.

I love you all. Yes, even you, the one currently furiously typing a rebuttal.