It was 1979. I was seven. Class II. Air Force School, Agra.

For my birthday, I was gifted a dark blue Hero cycle. My very first. It was a “Lady’s Cycle”, meaning it lacked the horizontal rod, but it was mine. And that was all that mattered.

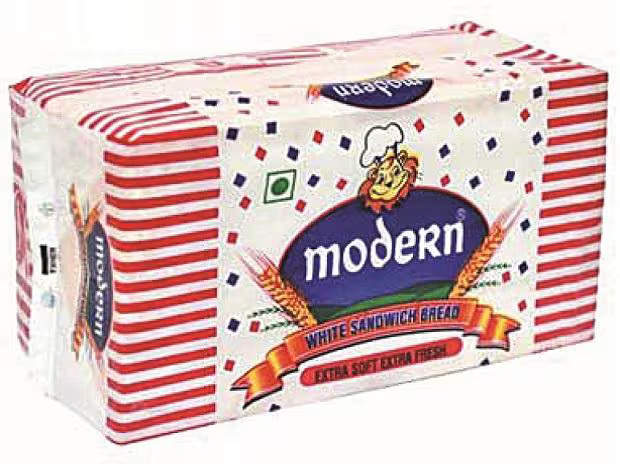

I didn’t know how to ride. But I was determined to learn. Within 24 hours, I had “mastered” the basics: getting on, pedalling, and staying upright. With confidence (and ambitions) far exceeding my skills, I asked Baba for a task. He handed me Rs.3 and sent me off to buy a loaf of Modern Bread from the corner shop.

What Baba didn’t anticipate? Bread cost Rs.4.

What I didn’t anticipate? Brakes.

At the shop, I managed to stop—barely—by dragging my feet. I learnt the price of bread, realised I needed another rupee, and set off home again. This time, at full speed, I encountered the laundryman. He turned into our compound. And stopped. I couldn’t.

The laundryman and I both learnt about momentum that day. I still have a scar on my left knee to prove it. I suspect he has one, too. Without the story, though.

But this isn’t a story about that.

This is a story about the story I wrote about it.

Our teacher, Kulwinder Kaur, used to tell us stories with morals. She was great at it. After every tale, she would explain the “moral of the story.” I was intrigued. What’s a moral? “A useful lesson,” I was told. Naturally, I misunderstood. To remind you: I was seven.

Anyway, the assignment was to write a story with a moral. I wrote about the bread incident. My masterpiece read:

“One day, Baba gave me Rs.3 to buy Modern Bread. The shopkeeper said it cost Rs.4. I came back, took another rupee, and bought the bread. It was a good bread. This is a good story. The moral of the story is that Modern Bread costs Rs.4.”

The teacher was… unimpressed. She explained, at length, what a moral is. I nodded dutifully but remained unconvinced. To me, it was useful information. Surely that qualified as a moral?

Eventually, I gave up trying to understand. “Morals” seemed unnecessarily complicated. To be honest, I still think they are.

So, why am I telling you this?

I don’t know. Should I connect it to my emotional growth and post on Facebook? Or extract some deep lessons about perseverance or sales strategies and put up a ‘What I learnt about B2B sales from the price of bread in 1979!’ on LinkedIn? Should I allude to some happening trend or news we could all learn from?

Probably not.

Sometimes, a story is just a story.

And the moral of this one is that Modern Bread cost Rs.4 in 1979. I thought you should know.

You are welcome.

P.S.: Speaking of misunderstood concepts, let me address another issue. Many people today claim that the em dash is definitive proof of AI authorship.

Newsflash: I have been using em dashes ever since I started reading The Economist in the 2010s. I picked it up as one picks up British humour. By osmosis. And a lack of better judgment.

And now, thanks to these self-proclaimed sleuths, I avoid using it. Not because I think it is improper. But because, apparently, punctuation is now a litmus test for authenticity.

Which, if you think about it, is as absurd as claiming a love of ellipses means you were trained by… Shakespeare.

So, here we are, with a scar, a loaf of bread, and a lingering fear of punctuation police. What a life.

P.P.S.: About the actual price of bread, I may not remember it accurately. What I do remember are the incidents of (1) my cycle crash with the squadron dhobi and (2) my story (and the teachers’ reaction) about the price of bread as a ‘moral’.

The rest may or may not be accurate. The price of bread might have been Rs.2 or maybe Rs.3, or whatever. That is not the point here. I thought I’d make that clear before someone starts disputing the actual figure, which, in this case, is immaterial (I had several people in my DMs telling me how they remember the price differently; and not one of them had a figure that matched anyone else’s!). It’s the story that matters.