Yesterday, I was accused of two things:

-

-

- That I create drama so I can write about it and share it with the world.

- That I break laws and rules arbitrarily and my proclamations of moral righteousness in what I write are but posturing and virtue signalling.

To the first, I plead not guilty and will fight it tooth & nail.

To the second, I am willing to take a plea bargain without admission of guilt.Let me explain.

There is life. It is around us. All of us. It is full of drama. Some of us can see some of it. Some of us can see more and some less. Some of us can’t see any. Some of us who can see some of it can write. Some of us who can see some of it and can write choose to write about it. Some of us who can see some of the drama this life has and write about it and choose to do so, publish their work, whether formally in a book or magazine or on social media. I am one of those. Some of us like to read about the drama we miss about life written and published by someone whose writing we like to read. You, my dear reader, are one of those.

If you could write, and chose to, and published what you wrote, the source from which you would derive your material would be your life and the lives of those around you. If you did, you’d realise that drama is all around us. And people like me can see it, describe it, choose to do so, and then publish it for you to read.

We don’t create drama to get material to write. Not because we can’t. Possibly, if we try, we may be able to do that to a lesser extent. But more because we do not need to. There’s enough to go around. And then some.

It is preposterous to suggest that I intend to, or am even capable of, creating drama just so that I have something to write about! Isn’t life already unpredictable and dramatic enough for us all?

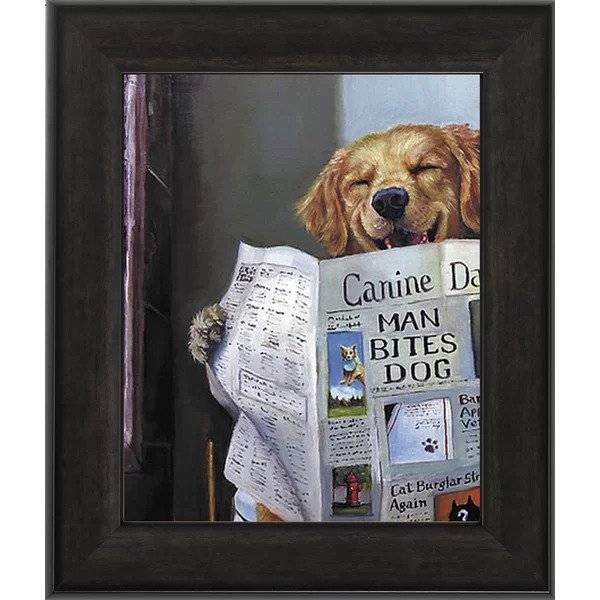

All I do is simply observe, listen, engage, and absorb the goings on around me and to me, and then, when I spot something interesting enough to share (like this article you are reading), I write about it and publish. Indeed, there is a reason why writers prefer to write about drama and never about normal things. Because you wouldn’t read it (maybe I have written about boringly normal stuff and you couldn’t go past the first para; how do you know how much of my writing you’ve missed out or skipped?). And it won’t be fun writing about it. As they say in newsrooms, dog bites man is not news, man bites dog is. Or was it, ‘If it bleeds, it leads’?

That’s my answer to the first charge.

Now, to the more complex second charge.

My life is not perfect. Nor am I. Indeed, no one is. Despite claims to the contrary. I live in this world. With its corruption (of every kind), with its large and small temptations, with opportunities to game the system and cut corners, with low-hanging, but forbidden fruits. I am, at the end of the day, human. I break a minor law here, bend a rigid moral code there, compromise on my ethics someplace else, cheat on myself a bit, break a promise, breach a commitment, look the other way, and betray my own ideals perhaps on a daily basis.

The issue, to me, is this: Does my not being perfect disqualify me from holding an opinion about what we ought to be, what we must aspire for, and what the ideal society must look like? By what degree is a message diluted or distorted by the messenger? I believe that depends. A Salman Khan preaching about drunk driving or ecological conservation, a Narendra Modi speaking of non-violence and tolerance, an Elon Musk speaking of workers’ rights, or his father speaking on incest are some quick examples I can think of where the messenger matters as much as the message. But, a chain smoker speaking on the ills of smoking, an obese and fast-food-loving cardiologist warning us against the dangers of cholesterol, a dentist with bad teeth telling us the virtues of good dental hygiene and aesthetics, an alcoholic writing about liver cirrhosis, are all examples where the gravity of the message and its import is neither lessened nor warped just because the messenger seems incongruous to it.

Similarly, unless my moral turpitude is of such degree as to misrepresent the message or invalidate it, I think I should be allowed to say it, write about it, and defend my stand. The ideology I expound and defend is so much larger than my own human foibles that it beggars belief that anyone would confuse the two.

I would invite my readers to focus on the message in my case without allowing their personal prejudice about me as a human being colour their perspective.

After all, let those who are without sin cast the first stone.

-