How much do clothes matter in human-to-human interaction? A lot, I’d say. They are not just simple garments that are used to regulate body temperature in place of fur, which we have lost about 1.2 million years ago when we decided to stand up on our own two feet. They are locators of our socio-political status, religious beliefs, personal tastes, and the markers of where we are in place and time (and not just the time of the day, but our times, as in historical times). In that way, they serve as extensions of our personality and therefore, define and identify us in ways that are not always apparent. In an ideal world, at these temperatures and with this weather, most Indians would need no clothes more or less through the year, or at least not as many as we wear every day. That is if clothes only served a utilitarian purpose. But they don’t. They are so much more.

How much do clothes matter in human-to-human interaction? A lot, I’d say. They are not just simple garments that are used to regulate body temperature in place of fur, which we have lost about 1.2 million years ago when we decided to stand up on our own two feet. They are locators of our socio-political status, religious beliefs, personal tastes, and the markers of where we are in place and time (and not just the time of the day, but our times, as in historical times). In that way, they serve as extensions of our personality and therefore, define and identify us in ways that are not always apparent. In an ideal world, at these temperatures and with this weather, most Indians would need no clothes more or less through the year, or at least not as many as we wear every day. That is if clothes only served a utilitarian purpose. But they don’t. They are so much more.

In certain professional settings though, clothes are designed to extinguish the individual identity and enhance the sense of community in an exclusive closed club-like setting, where not just the members themselves, but other outsiders can easily identify those who are in-group and those who are not. These are called uniforms and are seen regularly in the military, police, schools, colleges, and similar exclusive clubs, where they may constitute the entirety or a part of the full dress, facial and other hair, nails and makeup, footwear, and headdress of the member of that particular club. Some of these are very strict, to the point of ridiculousness (there is an Indian airline that once imposed a wig on their women cabin crew to enforce a homogenous look). Some are very specific (even oddly, for the 21st century), but have traditional backing, for example, each type of dress (uniform) in the military has a name and a standard code number which is cited even in invitations to parties and other formal events, as to what the officer is expected to be wearing should they wish to come. Some are more generic in their approach (as a member of my golf club, I am expected to wear a cloth-based collared shirt without slogans or messages (political or otherwise) printed on it, tucked into a full- or quarter (below the knee)-length cloth trousers with a belt, and proper shoes to appear on the course. Some others, of course, are even more open to interpretation, and are getting more and more loosely defined with time, for example, what passes as office-wear today is what would be called ‘semi-formal’ or even ‘smart-casual’ at one time.

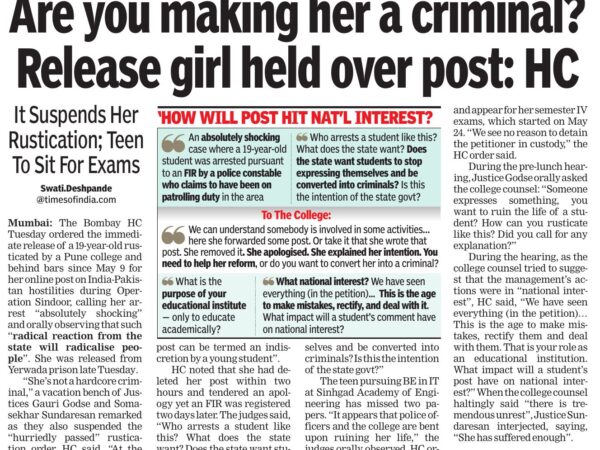

The recent happenings in Karnataka where a bunch of hijab-wearing (for now, let us forgo the nuances between hijab, chador, burqa, niqab etc., though there is enough online that you can access with a single Google search) schoolgirls were stopped from attending school because they were not wearing the uniform raises several questions in a democratic, secular state with a written-down, government-guaranteed fundamental Right to Education.

- If there is a requirement for a uniform, why were the girls admitted to the school without this being made clear?

- Does this uniform take into consideration religious symbols like crosses worn or tattooed on their bodies by Christian students, long hair, pagdis, patkas, and fifties worn by Sikhs, holy threads (whether on the wrist or across the torso) and tiles & tikkas (even bindis) worn and ‘Om’ and other religious symbols and totems tattooed on their bodies by the Hindus, and so on?

- If the uniform takes into consideration, and allows for an exception for some, or all of the above, then what is the overarching requirement that is a deal-breaker? Is it security? Is it positive identification? Is it avoidance of unfair means in an exam? Is it a combination of some or all of the above? That means, for example, a pagdi worn to tie down long hair, if tied tightly enough to not allow for hiding a cheating chit in an exam, and if it shows the eyes, ears, nose, lips, and other facial structures enough to identify the said student positively as what he claims to be (so as to stop impersonation and those that are not enrolled as valid students in that class/school to attend it), whether or not it has the sanction of his religion behind it, would be allowed, but a dress, with or without religious sanction, that impedes attempts at positively identifying someone or allows hiding cheating material in an exam in places difficult to search, reach, or police, would not be.

- How does the requirement to wear a face mask (and N95, no less, as per recent ICMR guidelines, if I am not mistaken) at all times, as per the pandemic rules and guidelines, and for the safety (as demonstrated by science and accepted by the government, the examination board, and the school), square with this circle? How can one differentiate between a student wearing a Covid-appropriate face mask and another wearing a religious veil from an objective, impartial perspective? So, is it a requirement to take off the face mask from a safe distance to positively identify the student when asked for such identification? In which case, would the same work with a religious veil? If yes, and female Muslim students wearing a face veil (which, by the way, is not what a hijab is, which is simply a headscarf, much like the Sikh pagdi, but that, as I said is another discussion), how are they different scenarios?

- Now, let us go back and see Point 3, and add one more question to why this school (or any school) has a uniform: Is it to foster a feeling of joint community that erases race, class, and caste hierarchies and allows the students to see themselves and other students as part of something larger than them, as something that is equitable and the same for all? I’d say, this should be the top (and perhaps the only) reason. I also believe that the institution should provide such a uniform within the fees it charges (or the aid it receives) just like a mid-day meal so that rich students and poor students do not have the same uniform but with different material, stitching, and styling that distinguishes between them even when they look like wearing the same thing. In such a case, and only in such a case, where ALL religious imagery is abolished, can the school insist on the hijab-clad girl students to be removed or denied entry for lack of meeting the clothing standard? And in an ideal world, that would be how it is. A free-to-choose school exercising its right to enforce a code that is not illegal and was made clear to any applicants before they decided to join the said school. Just like it can have competition from another free-to-choose school nearby which has a ‘no uniform’ policy. Or another school where the hijab is compulsory. Or another where some other standards apply.

Unfortunately, we don’t live in an ideal world. This is only possible if everything was equal and all things were the same, we all had equal opportunities, privileges, and agency, and if our culture and our society were evolved to a point of individualism (in all its manifestations, including fashion and identity) living in harmony with the common good, like how a perfect capitalist-democratic-social welfare state (somewhere approximately around where a Sweden or New Zealand has reached today) should be. But, and I don’t need to say this to my intelligent reader, this looks good only in theory. The reality is far from it.

So, even when I agree that such and so should be the case, we need to take into consideration that belief is not something that can be enforced. I may be an atheist and believe that religious symbols, be it a pagdi or skull cap or a cross in a pendant or a holy thread tied to the wrists, should have no place in an institution where a uniform is defined and required. Just like one should have the freedom to join, or indeed even start, a school where it is mandatory to flaunt one’s religion, as long as there is freedom of choice and opportunity for all. But I cannot be blind to the fact that India does have a majority that believes in religion and sees their identity in it to the point of ensuring that such identity is seen by others (their own kindred or others outside their community) through a choice of clothing, symbols/marks, and/or hairstyle. This becomes even more important when the said community is a minority one and is being persecuted openly by the majority with the tacit approval, and even encouragement, by the mainstream media and the government of the day, the head of which openly calls himself a ‘Hindu Nationalist’ and its choice for the head of the largest state wears saffron robes to office, doubling as the temporal head of a religious shrine while he holds public office in a secular country. What one’s identity means in such a scenario possibly cannot be explained. It might only be experienced. And I, a cishet educated urban-dwelling high-income Brahmin male, am unable to either understand or feel what they are going through.

But, as my friend Amit Schandillia has said so well, ‘Victimhood is no immunity from criticism. Privilege is no forfeiture of opinion.’ And that means that while I may be privileged, I am allowed to have an opinion on things that my privilege may be blinding me from prima facie, but my intellect may be sharp enough to cut through and have as clear-headed a view as is possible under the circumstances. Also, I believe that victims are biased in their own way when looking at their situation, and oftentimes, it helps to have an outsider looking in, for gaining perspective, if for nothing else. As Prof Galloway puts it rather succinctly: ‘You cannot read the label from inside the bottle.’ You need, sometimes, a person on the outside, who can read it to you. What you do with such information is, of course, up to you. No one can force your decisions. But the perspective it brings will most definitely add value to that decision you finally take.

So, here’s mine: Actually no. I won’t tell you what my opinion on this matter is. I want you to read, think, and make up your own minds. I think I have given enough material above to think about. So, this time, you go first. What do you think about the situation as is unfolding in Karnataka where a group of hijab-wearing girl students were barred entry on account of their hijab? What you think about this is important, since you are the educated influencers of opinion of your community and this society. You need to take all the points I noted above into consideration, but there is one more you need to think about. It is this: If whatever your opinion is, if this advice is implemented across the country, like a formal law, like the gospel truth, and everybody were to follow it, would it end up with the world and this country, your society, your people, being better off? Or worse?