|

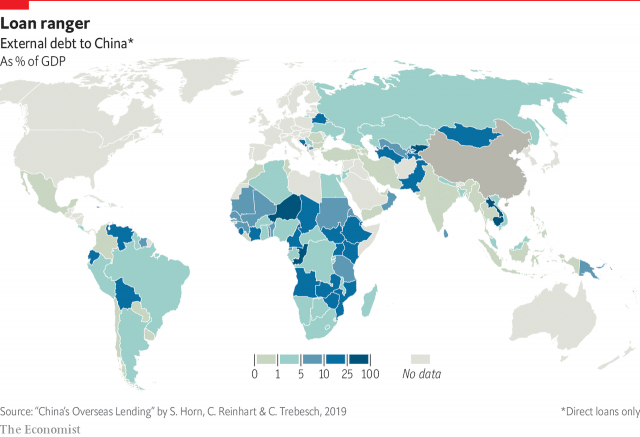

| Image Credit: The Economist |

Last year, in December 2018, fisherfolk from a small coastal town of Gwadar protested the construction of a 6-lane highway that would have cut off their access to the sea through the bay, and affected their traditional livelihood directly. It made national news and much was written about it in the media, though in the end, the protestors were removed and the construction continued.

In recent news, Sri Lanka’s new government led by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa says it wants to undo the previous regime’s move to lease the southern port of Hambantota to a Chinese venture, citing national interest.

A question for those who are experts in this sort of thing: What happens if the Sri Lankans simply decide that they cannot give up the port in the (strategic) interest of their nation, to a foreign power like China?

Other than an economic blockade and an international arbitration/trial that would seek to overturn the decision to nationalise the port, what could China do? Military action? How would that pan out if multiple borrowers like Pakistan and several African and Asian nations defaulted, had coups or changes in government, and the new leadership nationalised the assets? How many countries (and markets) can China remove itself from? How many wars can it fight?

And what happens if neighbouring countries or competing powers (either regional or international) see the takeover of a strategic asset of their neighbour/partner as a threat to their own security, whether political or economic and enter the fray as “protectors” or alliance partners of the defaulter? Things can get so hairy and intractable for China if this happens (as I suspect it will) that the ruling elite in China should be worried about the political fallout of the massive and inevitable blowback of these situations outside Chinese borders causing ripples inside their country.

|

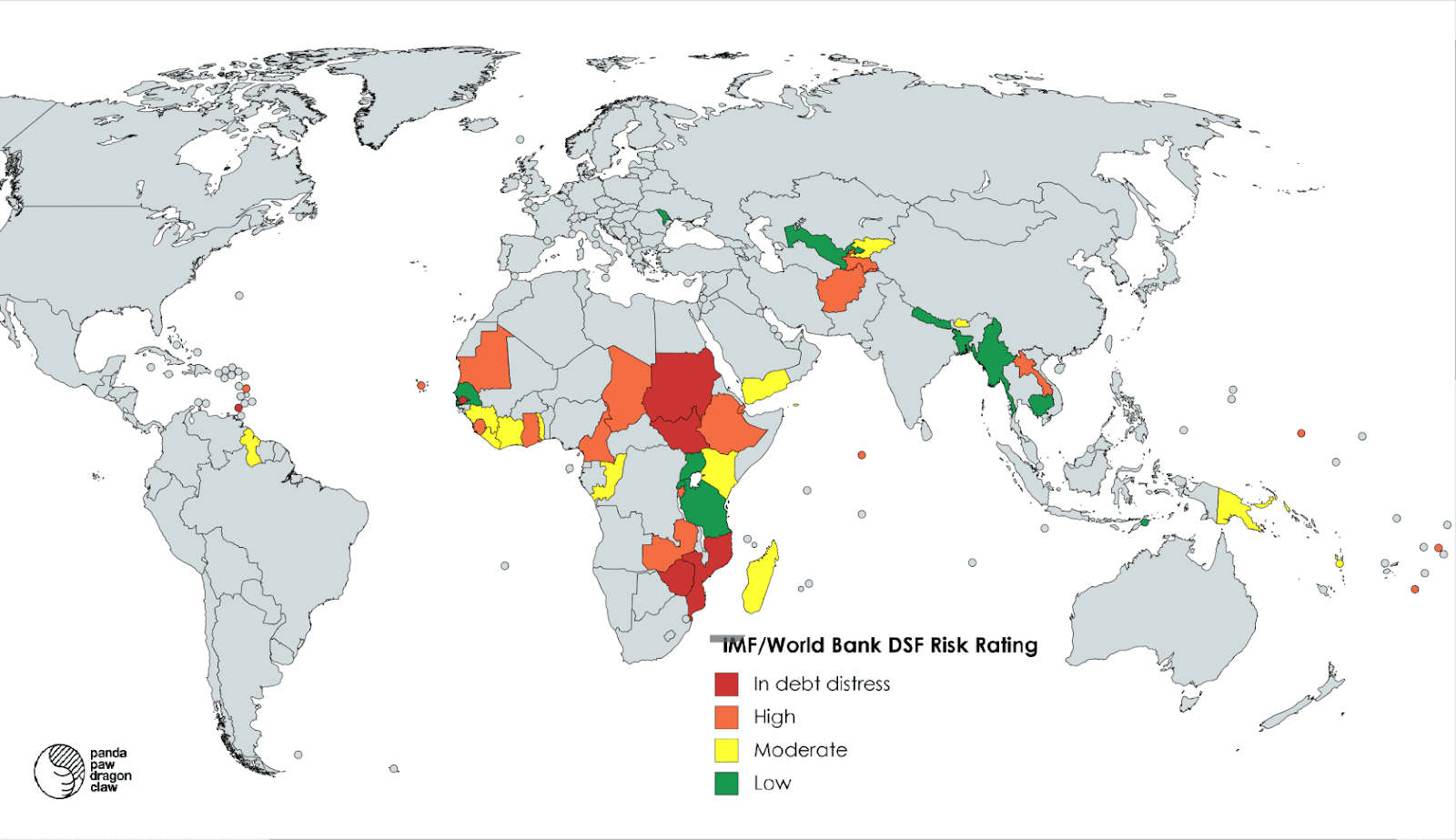

| Image Credit: Panda Paw Dragon Claw |

I’ve been thinking about this ever since I read about the OBOR and CPEC, and specifically the huge loans and credit lines China is forwarding to economies that simply do not seem to be in a position to repay, nor the wherewithal to sweat that asset in any form.

It’s like giving a marginal farmer with a couple of acres of land, a combine harvester on lease against the mortgage of their land, and then, once the farmer defaults, as he surely will, taking away his land AND the harvester, and then making him a tenant on it to keep tilling the land for the new owner. The basic idea hasn’t changed much since the East India Company days, but the pig looks different because he’s wearing a new colour on his lips.