As the people cheered for their King Emperor, resplendent in his finery, riding atop the royal elephant, with his Dewan sitting besides him, dressed similarly, a small child of a poor mother shouted, “But he is naked! He has no clothes! The King has no clothes. Nor does his Dewan.”

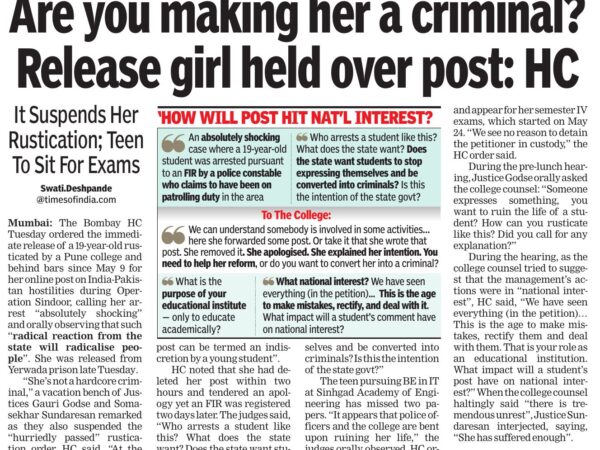

The Dewan looked with displeasure at the knee-high girl in rags, and shouted, “Seize her.”

Suddenly, tough-looking soldiers appeared from nowhere and, pushing aside the girl’s mother, picked up the child and stuffed her into their carriage.

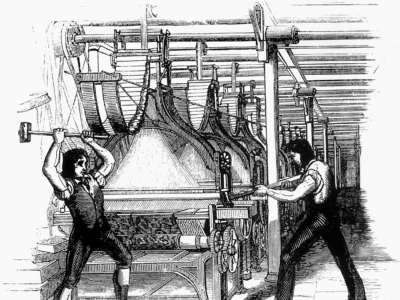

The King sent out a royal firmaan. He directed all the courtiers in the King’s bejewelled court to change the cloth of their courtly dresses and costumes to this fine, expensive, and invisible (to the unpatriotic) cloth made by the Dewan’s friends, the weaving chiefs of Amb and Ad, from his native state of Raat.

The next step was to command all the local chieftains owing their allegiance to the King to switch to this magical cloth. Soon, the soldiers of the Kingdom were ordered to change their uniforms to adhere to the new dress code.

The citizenry needed no instructions. The more patriotic of them broke into and exhausted their life’s savings to acquire the new dress to show their love for the King and their nation. They forced their families to follow.

Some people protested. But they were put down by force, stripped off their clothes, and paraded on national media where they claimed, through their broken teeth and blackened eyes, that all was “normal”.

Soon, the only people left wearing regular clothes that were visible to everyone were the so-called skeptics and intellectuals, who were jeered and mocked with slogans that called their anti-nationalism out. This last bastion (the kapde-kapde gang) was finally turned using a combination of public shaming, excommunication, coercion, and the simple fact that the cloth of their choice (the regular, visible one) simply disappeared from the shelves in the marketplace, given that all the traditional weavers either went out of business and starved, or joined the weaving guilds of either Amb or Ad, who paid poorly, but were the only acts left in town when it came to fabric.

The entire Kingdom was now “clothed” in the new nakedness. What’s more, each of them were proud of the fact that they were now somehow better off than before (“The previous rulers did nothing in the last 700 years,” was the constant refrain). The King’s and Dewan’s popularity knew no bounds as people loved the newfound “respect” other nations were giving them, even if their chief export (fabric) was no longer accepted by any markets outside their own, and even if almost all the citizens had lost their jobs because the shutting down of the weaving industry and most had to go without food for extended periods of time. The refrain was, “So what if we are hungry? At least we are gloriously dressed. No one before this King had dared to dress us up in royal fabric. We are finally free of our fetters that tied us to the unpatriotic version of fabric defined by outsiders.”

The world laughed. People starved. The weaving chiefs of Amb and Ad got fatter. The King and the Dewan strutted like peacocks, cheered on by the starving, naked people. And then, one day, the little girl’s mutilated body was discovered by the riverside.