This first appeared on LinkedIn.

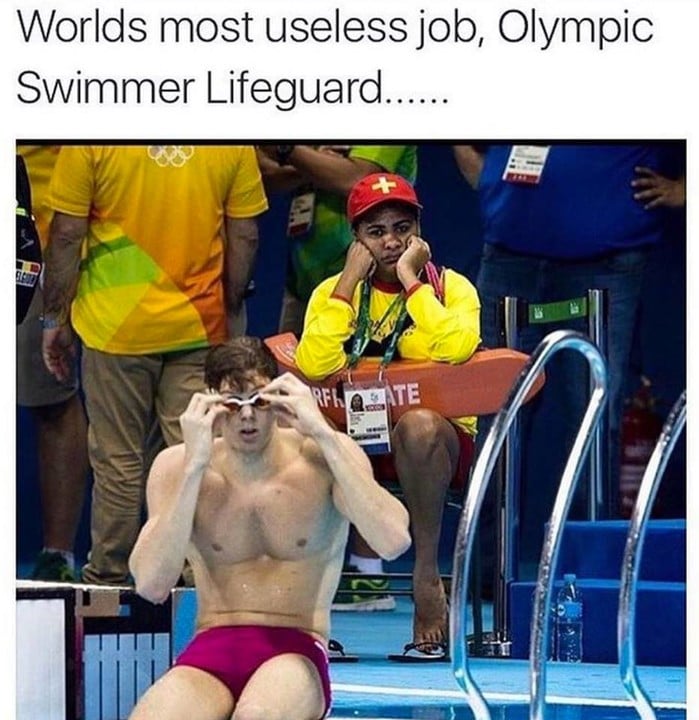

J Jagannath, a freelance journalist, who writes mainly on Indian cinema, published this absolutely bang-on rant on 06 June 2018 about the uselessness of Indian mall security and the “security” paranoia we all seem to have, most of it unfounded.

It got me thinking.

To be honest, I couldn’t have put it better. I have asked myself this a number of times myself and the only answer I can think of is that it is a throwback to the colonial times where the natives weren’t to be trusted and every place was “Restricted” and photography was prohibited everywhere, while every document was “Top Secret” and everybody was a potential suspect in a future crime. But then I look back at the pre-colonial times and see that the feudal lords had a similar view of the peasants under them and perhaps the Brits just decided not to fix what wasn’t broken according to them. So, maybe this goes a long way back.

Coming to the frisking and metal detector checking in malls, my father, an IAF veteran had an observation that made sense to me. He said that while those poor, underpaid, overworked security guards were not even trained to know what it was they were looking for, they seemed to have an irrational belief bordering on the superstitious, that the handheld metal detector they carry around and wave at your body is some kind of a religious totem with magic powers to ward off evil automatically. It’s less about whether it detects anything and more about some sort of “shuddhikaran” (a ritual cleanse) that the whole waving it about achieves thereby negating through some religious mumbo-jumbo any bombs or contraband that the subject of this wand-waving might have on their person. To them, it wouldn’t matter if instead of the metal detector, they had a bunch of smouldering agarbattis in their hand and instead of their uniform, they were asked to wear a dhoti and a janeu and shave their heads (except for the shendi/pigtail). Literally, no difference.

Come to think of it, that would have been funny if it weren’t so close to reality.

A lot of the jobs we do as employees, or create as employers, have the same characteristic. We might have had a purpose for the specific piece of activity when we first visualised it and put it into motion. We might even have had the right intention, and perhaps in the initial days, it might even have achieved parts of the stated purpose. But as time has gone by, many of these activities that seemed the right thing to do at one time, start losing their connection with the original objective, or in fact, with reality itself, and become so stupidly mechanical that in the best case, they result in no contribution to the business we are in, and at worst, become a burden dragging the business and its profitability and efficiency down, making it more and more unviable until the whole damn thing implodes, with us trying our best to keep doing each of these useless tasks right till the last day that the business operates before shutting down. We wonder why, even when we were doing everything, working very hard, and sticking to the processes, did the business go under. And unfortunately, even hindsight does not bring clarity to the past because we often fail, and sometimes refuse to see the percentage of our activity that was totally pointless and without any contribution to the movement of the business towards a better enterprise.

One way is to have regular process audits, and ensure that each task has a specific purpose with measurable results and that this purpose is relevant today (and possibly tomorrow) and that by continuing to do this task, we are not taking resources away from another task of more importance, or aren’t hindering in the execution of a more important task.

But an even better way to ensure that we do not continue to do irrelevant things is to train yourself and your organisation to be more self-aware of things we do every day as part of our jobs. By doing so, each stakeholder doing any task for the organisation will do it with an understanding of what they are doing and how what they are doing is contributing to, and not hindering in, the short, medium, and long-term goals of the organisation they serve.

This is easier said than done. if you figure out how to do it, let me know.